The fall of Reza Khan and the compilation of Kashf al-Asrar (The Unveiling of Secrets)

Reza Khan’s departure from the country was happy news for many Iranians. It is no exaggeration to say that this event was a national celebration for the people of Iran. the Imam has recounted his unforgettable memories from those days, time and again:

I myself was a witness to this when the armies of three countries invaded Iran and everything was exposed to danger, the people still rejoiced. It was as if they were celebrating the arrival of the Allies, but they were rejoicing because they had been told that the Allies had sent Reza Shah away! (Sahifeh-ye Imam, volume 4, page 355)

The fall of Reza Khan’s dictatorship was the longtime wish of all of the oppressed people of Iran. However, immediately after his fall until years later, no clergy or non-clergy leader emerged in the country’s political arena in order to lead and organize the people’s self-initiated movement and to transform it into a full-fledged anti-despotic revolution and rid the country of the monarchy. The Imam’s sorrow too was due to this.

Regrettably, at that time there was nobody among the nation to bring the people together and lead them. So, they installed the son of Reza Khan here. If that time, two or three cities had demonstrated against him, they would have not placed Mohammad Reza in power. But nobody uttered a word as that fear had gripped the people, and had not left them. For that reason, the people did not have the courage to say anything. There was also nobody to compel them to do so. Had the late Modarres been present at that time, he would have done something. But there was nobody around to do all these things. You are aware of most of these matters that I am relating to you. (Sahifeh-ye Imam, volume 13, page 326)

Numerous political guidelines can be seen in a note by Imam Khomeyni written on the 11th of Jamadi al-Awwal 1363 AH, 15th of Ordibehesht 1323 SH (5th of May, 1944). In this document, after presenting a short introduction, the Imam goes on to consider and analyze the past, present, and future condition of the people. In the introduction, he recognizes “rising for God’s sake” as “the only way for world rectification” which was the philosophy of all the divine prophets’ missions, from Adam to the Seal of the Prophets (PBUH); he then goes on to explain the reasons for the adversities of the Muslims and the people of Iran.

Selfishness and abandonment of rising for God’s sake have made us this wretched, and has caused the whole world to overwhelm us and has brought Muslim countries under foreign influence… It is rising for the individual’s sake, which caused an illiterate Mazandarani (meaning Reza Khan) to prevail over a group of millions, letting him exploit their offspring and estates to his lustful ends. Rising for personal interest is the reason why some street kids (meaning Reza Khan and his accomplices) have now gained rule over the Muslims’ belongings, lives and honour. (Sahifeh-ye Imam, volume 1, page 16)

Elsewhere, he addresses and reproaches the scholars and clergymen, enumerates their heavy responsibility, and reminds them of the consequences of their political negligence.

Today is the day when the spiritual divine zephyr is blowing and it is the best time to rise for the reformation; if you miss the chance and don’t rise for God’s sake and restore the religious rites, a bunch of lustful vagabonds will prevail over you tomorrow and exploit all your faith and honour to their own vain ends. What excuse do you have in the presence of God today?... What is this weakness and misery that holds you?... When you failed to rise for your legal right, the obstinate secularists got up and began silently to advertise against religion from every corner and in no time they will prevail over you, who are stricken by disunity therefore, you’ll have harder times than during Reza Khan’s period.

(Sahifeh-ye Imam, volume 1, page 17)

the Imam believed that the political circumstances in those days had completely made possible the occurrence of an Islamic revolution like the 1979 revolution, and thus he lamented the historic opportunity which had been lost, so much so that he even recalls it despondently in his will.

Alas, this revolution took place rather late! Had it taken place even as early as the beginning of Mohammad Reza’s rule, this pillaged country would have been something else today.

(Sahifeh-ye Imam volume 21, page 443)

However, just as the Imam himself points out, the emergence of such a personality didn’t seem possible with the repressions, killings, exiles, and suppressions that faced all combatant clergies and non-clergy freedom-seekers throughout the rule of Reza Khan. What can be said about the clergies is that the pressures and political, social, and mental straits which were together with propaganda and scandals against them, completely kept them aloof from the political arena and had formed the same delusion in their minds. Thus, in the political circumstances after Reza Khan, the clergymen were happy with the religious and social freedoms which were brought about and were not eager to lead a movement. Even a famous religious authority like HajAgha Hoseyn Qommi who had been exiled to Karbala in 1935 because of protesting against the “hat change plan” did not show any immediate tendency to return; he returned to the country two years after Reza Khan’s eviction. Upon his entry to Tehran in 1943, he had five requests from Soheyli’s government which included: women’s freedom to choose the hijab, doing away with mixed schools, holding congregational prayers and having religious education in schools, lowering the burden of economic pressure on people, and finally freedom of action for the Islamic seminaries. But Soheyli’s government paid no attention to Ayatollah Qommi’s requests.

This stance was a sign of heedlessness to Ayatollah Qommi and an implicit confirmation of Reza Khan’s anti-Islamic plans; thus, it caused some of the scholars to be offended and angered. Ayatollah Boroujerdi who was residing in Boroujerdi at the time sent the government a threatening telegram asking for the acceptance and enforcement of Ayatollah Qommi’s proposal. The government was well aware of Ayatollah Boroujerdi’s spiritual influence in Lorestan and was worried that in case of not sending an appropriate response to his telegram, it would lose control of the region of Lorestan, just like Kordestan and Azerbaijan. Thus, it formally accepted Ayatollah Qommi’s proposal and he left for Mashhad. Ayatollah Qommi’s proposal did not include any new matter; he consented to these limited reforms and did not object to the government anymore.

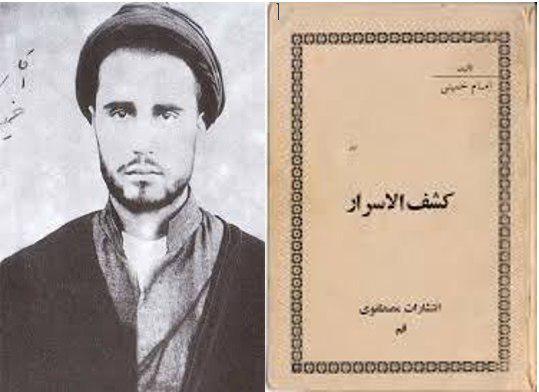

Another aspect of the Imam’s political activities in these years is the composition of his valuable book titled “Kashf al-Asrar.” Due to the importance of its political material, we will briefly survey it.

Kashf al-Asrar

In the year 1943, a pamphlet titled “The Thousand-Year Secrets” was published. Its author, who was influenced by Wahhabi ideology and the critical thoughts of Ahmad Kasravi, raised numerous criticisms against the Islamic clergy system and some Shi’ah beliefs, calling them superstitious. The publication of this pamphlet caused a lot of upheaval in Islamic seminaries, especially in the Qom Seminary, because the author himself was the son of a famous scholar in Qom and he himself was a former seminarian. Many clergies believed that this meant the infiltration of Kasravi’s thoughts into Islamic seminaries and could bring about negativity and great intellectual deviation among young students.

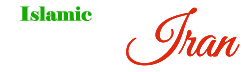

In those days, the Imam held ethic lessons. One day, on his way to Feyziyeh School, he encountered a group of seminary students discussing “The Thousand-Year Secrets” pamphlet. Thus, after buying and reading the pamphlet, he discontinued his ethics lessons and wrote the book “Kashf al-Asrar” in refutation to the mentioned book, in a month and a half or two months. To keep from fame-seeking, the book was published without the author’s name; however, after a while, some of the elites and later most of the clergies recognized the author. Anyhow, Kashf al-Asrar was the most important and rational response given to the issues brought up in “The Thousand-Year Secrets.” This book which was written in a short time is itself illustrative of the depth of the Imam’s information in the fields of philosophy, theology, and jurisprudence.

In this book, the Imam goes on to criticize and refute Reza Khan’s despotic government and the government structure he left behind, through theological, jurisprudential, historical, and political proofs; on the other hand, he goes on to present a new plan of an Islamic government on the basis of “Wilayat al-Faqih” as the only acceptable form of government. Many believe that the Imam mentioned the issue of Wilayat al-Faqih for the first time in his fiqh lessons and later in his book “Kitab al-Bay’”, while he had clearly and explicitly spoken about this issue 25 years earlier in his book Kashf al-Asrar. A number of points must be kept in mind while studying this matter:

- The Imam brought up the issue of Wilayat al-Faqih at a time when there was no evident and active inclination on side of the clergies toward political issues and the people’s national and anti-colonial movement had not yet begun.

- This was the first book that was written about leadership and Islamic government after the fall of Reza Khan, although it also includes more general topics; unfortunately, Iranian and foreign researchers have not mentioned it in their studies.

- Political literature in those years in criticism of western colonialist policies and culture was generally written from a Marxist party (Stalinist) or nationalist perspective.

- Due to the repression and anti-Islamic policies of Reza Khan’s government, and later due to the political circumstances of the time of war (World War II) and the occupation of the country, it seems very unlikely that the clergy of Iran was aware of the political changes in the world of Islam and the political views of the Muslim scholars and intellectuals of their time, at least during the two decades prior to it. This awareness and communication was realized a few years later, with the formation of the Israeli regime and the activities of Ikhwan al-Muslimin in Arab countries.

- Unlike many of the scholars and politicians before and after him, the Imam revealed the conspiracies of colonialism against Islam, Muslims, and the clergy and also sharply attacked and criticized Reza Khan’s anti-Islamic policies. Generally, the Imam considers Reza Khan as the candidate and executive of the colonialists’ mandates and does not separate and differentiate these two from each other, whatsoever.

- The Imam’s invitation is a return to Islamic identity which has been forgotten over the centuries of the kings’ despotism, the scholars’ negligence, and the distance of the Muslims from the fundamental teachings of Islam. This invitation is not merely an intellectual and cultural revival which the contemporary Salafi movement proclaimed or what Iqbal Lahori longed for. Rather, it is an intellectual and political Islamic revolution which must be brought about with the leadership of wakeful and committed Islamic scholars, resulting in the formation of an Islamic government. It is for this reason that the Imam presents the idea of the establishment of an Islamic government and its general plan and even enumerates the agenda and duties of some of that ideal government’s organizations.

The model of Islamic government envisioned by the Imam and other Shi’ah jurisprudents differs from the model presented by Ahl al-Sunnah thinkers in terms of theoretical foundations and historic examples both in the past and in the present era. This was because the scholars of Ahl al-Sunnah in the past mostly attempted to justify the governance of the caliphs and sultans of their time and to legitimize their rule. Thus, they had no choice but to correspond their idealistic beliefs with the political circumstances of the time. Although some Shi’ah scholars at certain points in history displayed concord with the rulers of their time in order to guarantee the life and security of their followers, what differentiates Shi’ah expediency from Sunni expediency in such cases is that this coordination was, in essence, immediate and temporary exemptions; it never threatened nor weakened the Shi’ah fundamental doctrinal position which holds that all worldly powers and governments are illegitimate in the absence of an infallible the Imam.

On the other hand, the difference which exists between Shi’ah and Ahl al-Sunnah sources of political jurisprudence has caused a clear difference between the Imam’s model of Islamic government and the model presented by other contemporary Muslim thinkers and Islamic groups; this itself calls for a separate discussion. This does not mean that all Shi’ah jurisprudents believed in the establishment of an Islamic government; nor did they have the same views regarding the limits of Wilayat al-Faqih’s authority. However, among the recent Shi’ah jurisprudents, at least two can be named who had views similar to the Imam regarding the limits of Wilayat al-Faqih’s authority.

- The Imam’s Islamic government is based on rational and narrational reasons, rooted in Shi’ah jurisprudence, and springs from its political philosophy. No foreign element nor adaptation has taken place therein. Unlike some of his contemporaries (such as Allamah Na’ini), the Imam never attempted to legitimize the Western Constitutional Revolution with rational and narrational reasons.

- The Imam’s political philosophy is brought up in the context of his historical mystical wisdom and is also its logical outcome. In addition, the Imam’s civil policy (and in a broader sense, social practical wisdom) follows Islamic theological and human wisdom and is put forth in relation to principles of belief and not practical laws, unlike Islamic philosophers who limit civil policy only to practical wisdom and link it to pure reason. Thus, the position of the Imam’s “Islamic government” transferred from the realm of jurisprudence to the realm of theology and mysticism, which is its true position.

the Imam brings up the issue of “Wilayat al-Faqih” with reference to the principle of absolute divine authority and the conditional authority of the men of God in mysticism and Islamic theology and places it against merely human governments; governments that are brought about as a result of defective thoughts and under influence of individual and collective carnal desires, based on authenticating personal and collective material interests and an arrogant colonial relationship, although under various manifestations and titles.

After rejecting all nonreligious human governments, the Imam proceeds to prove the Islamic government as the only desirable form of government that works toward the prosperity of mankind. He begins this discussion with the issue of “Wilayat al-Faqih” and the commentary on the verse of “Ulul-Amr” (those vested with authority among you, Surah al-Nisa: 59).

“God Almighty has ordered the formation of an Islamic government…and because he has made it incumbent on the entire Islamic Ummah to obey the Ulul-Amr (those vested with authority), inevitably, the Islamic government must be no more than one government…” (page 109)

But who are the Ulul-Amr or “those vested with authority”? This question has been the place of wide controversial discussions in theological and jurisprudential schools of thought. After expressing the opinions of those who recognize sultans and kings as the Ulul-Amr, the Imam refutes this view through rational arguments and does not recognize “ignorant mindless plunderer tyrants” worthy of Imamate (leadership) and the position of Ulul-Amri (being vested with authority). (page 111) In response to the question that why some scholars entered the establishments of the tyrant sultans and kings of their time, he explains:

“We say that even if someone enters this same ruinous dictatorial establishment (of Reza Khan) in order to prevent corruption and to rectify the condition of the country and people, it is good and may even become obligatory at times.” (page 227) Then, he goes on to support this statement with a quotation from the high-ranking jurisprudent, Haj Shaykh Mortaza Ansari (may God bless his soul). (page 228) After these explanations, the views of Shi’ah scholars on Imamate and the issue of Ulul-Amr are described in detail.

Like many Shi’ah Jurisprudents, the Imam recognizes Ulul-Amr as the “authority of the mujtahid” or “authority of the jurisprudent” and presents adequate rational and narrational reasons to prove this point. (page 185-188) However, what he means by authority (government) of the jurisprudent is not an executive matter; rather, it pertains to the guidance and supervision of the entire system’s movement: “When they say the government must be in the hands of the jurisprudent, it does not mean that the jurisprudent must be a king, minister, general, or military official; rather, the jurisprudent must supervise the country’s legislative and executive branches.” (page 232) Supervision is not verbal guidance; it is a guarantee of enforcement. “We can’t move ahead by only talking… after the legislative branch, the executive branch must be at work…these two branches must be linked together and in union with each other…as long as these two are separated from each other, they cannot go after the purpose.” (page 213) Elsewhere, to bring the reader’s mind closer to the form of the ideal Islamic government, he compares it with the constitutional system. (page 233)

The jurisprudent may select another person or persons to manage the Islamic government, and in this case, it is obligatory to obey that person; however, this person or persons must satisfy the appropriate conditions:

(The prophet, Imam, or jurisprudent) can give permission to a person who “does not violate the rulings of God which are based on wisdom and justice, and the official laws of his country are the Godly heavenly laws, not European laws or laws worse than those; based on wisdom and the constitution, any law that is against the rulings of Islam does not possess legality in this country.” (page 189)

Islamic territory and laws are not limited to only one dimension of social life; rather “Islamic law has not overlooked anything in the process of the government’s formation, the enactment of tax laws, the legislation of civil and penal laws, and what relates to the country’s organization (from the formation of troops to the formation of offices).” (page 184) Elsewhere, he delineates the philosophy of the formation of an Islamic government and its pillars: “Can all these verses in the Quran about battle with the disbelievers and war for the Islamic country’s independence and conquest be accomplished without a government and formation?... The basis of the (Islamic) government is the judiciary and executive branches and the public treasury and for the expansion of (Islamic) reign and conquest, on jihad and for protecting the country’s independence and to repulse the invasion of foreigners, for defending the nation; and all of these are present in the Quran and Islamic narrations.

At the same time that the Quran is the book of law, it has endeavoured toward its implementation; and while it has determined the country’s budget in the best way, it has identified the task of conquest and the protection of the country’s independence.” (page 237-238) Then, he has fully explained the principles of Islamic laws along with jurisprudential reasons in judicial fields (legal, penal, and criminal), financial field (taxes and their uses) and army or military (volunteer or involuntary draft). For example, in the description of the types of Islamic taxes, he writes, “In Islamic law, there are several types of taxes, some of which are taken by compulsion and some are received voluntarily, and each must be briefly explained. The taxes which are taken through compulsion are of two kinds: the first is annual and perpetual taxes taken at a time when the country is at peace and is not subject to foreign invasion, or there is no revolt (disorder) in the country; the second is extraordinary taxes which are taken at a time of foreign or internal revolt. The taxes taken at this time does not have a limited amount and should be called ‘unlimited taxes’; because it depends on the decision of the Islamic government. And since this is an indirect tax, it is of course taken when direct taxes are unable to prevent revolt in the country. At this time, the government takes whatever it needs from the people. If it sees it appropriate, it takes it as a loan, otherwise, it is taken as an indirect and exceptional tax to the extent of the country’s need; of course, it is taken based on fair distribution. Even if the Islamic government needs to take the people’s entire property, it takes what is surplus to their necessities and spends it for the independence of the Islamic government.” (page 256) Then the five categories of direct taxes “that are taken for the country’s internal management, cautionary expenses, and state and army interests, which people must pay to the Islamic government” are explained in detail. (page 256-258)

The question that is brought up at this point is that are the Islamic rulings and laws specified in books of Islamic jurisprudence sufficient for the management of the Islamic government and its present-day matters or not? In the case that such needed, explicitly stated laws are absent in those areas, what is the responsibility of the Islamic government? The Imam writes in response that “of the [other] laws which the country requires over time are those which are non-contradictory to religious laws and play a part in the country’s present-day order and progress. The government can discern these laws through religious experts who can compare them with Islamic law and legislate them…even if they are not mentioned in Islamic law.” (page 259)

All Islamic laws have two aspects: material and spiritual; they take into consideration both the material life and spiritual life. “For example, just as the call toward monotheism and piety-which is the greatest of invitations in Islam- brings about the provisions for spiritual life, it is completely involved in material life and assisting the country’s order, social life, and the basis of civilization.” (page 312) Equally, material laws also have spiritual aspects. For example, “financial law in Islam for the management of the country and the needs of material life is legislated in a way that the spiritual life aspect is taken into consideration and is an aid for spiritual life. Hence, the intention of achieving nearness to God-through which the spiritual life is realized and the human spirit is developed- is a precondition in the payment of most forms of taxes. This is true about laws regarding the system, judicial laws, and other laws. This is one of the greatest masterpieces which is of the characteristics of this law.” This is exactly the opposite of “human laws which invite man toward this same material life and make him neglectful of the eternal life…” (page 312 and 313)

leave your comments