In the Name of God, the Most Compassionate, the Most Merciful

Author’s Note

“The Stories of the Revolution” is a total of about twenty in number, and children play the main role in all of them. These stories were sent to me or entrusted to me by children from different parts of Iran at the height of our sacred Islamic Revolution. They were either given to me through my acquaintances or were handed to me during my journeys all around Iran. In the climax of the Islamic Revolution, these stories couldn’t be typeset. I arranged six of them and converted them from the simple report form to story form; I wrote them out with a pen and published them. These kinds of stories were called “white cover” back in those days because no one had the time to design and publish a nice cover. After publishing these six volumes, the serious post-Islamic Revolution works began; I went to the Red Crescent Organization and worked day and night to start the “Red Crescent Volunteers Organization.” Afterwards, the entanglements and pressures of life didn’t leave me time to turn those glorious, bittersweet adventures into “stories.” I gradually arranged six more stories, but didn’t finish and publish them. The rest of the adventures and outlines were left unfinished.

This year (1994) the first five stories are being reprinted with the effort of “Hozeh Honari” in a beautiful format, along with illustrations. You are looking at it now. With hope in God, if I stay alive, I will publish the other six stories next year, on the anniversary of our great and glorious Islamic Revolution. And if I remain alive for more, I might publish the other eight in the upcoming years…

These stories, which are about the nooks and corners of the biggest Islamic Revolution in human history, are a dear memento; I want them to be left behind from me and the children who entrusted these notes and memories to me.

I had a faithful co-worker who helped me in the compilation of some of these stories and I would like to thank him. So, thank you, Mr. Shakour Lotfi.

And also, it wouldn’t be right to not thank the first publisher of this series; because back in those wonderful days, these kinds of works needed a lot of courage. So, with thanks to Farzin Publications.

Our Islamic Revolution was such that even if hundreds of big books were written about it, it would still not suffice. These few small books are a dim star in the clear and unlit sky.

Thank you and goodbye

Nader Ebrahimi

November 6th, 1993

Mansour was one of the kids who lived on “Delgosha Junction.”

One morning, when his father was leaving the house, he asked Mansour, “Are you coming with me?”

Mansour answered, “No, I’m going with the neighbourhood kids…”

And father didn’t say, “Watch out for yourself!” It had been a long time since that father didn’t say such things anymore.

Mansour was thirteen years old. And he didn’t remember his father asking him if he’s going with him before the Islamic Revolution. He didn’t remember his father giving him permission to go anywhere he wants with the neighbourhood kids. He didn’t remember being taken into account in the house and his opinion being asked about something or being allowed to choose his way himself.

He didn’t remember his mother saying, “Put a piece of bread in your pocket! It might take too long.” Or, “Be like everyone else! Don’t run away when no one else is running!”

No…he didn’t remember these sort of things at all. These behaviours and words all belonged to the time of the Islamic Revolution.

The freedom of going and joining the other kids, walking the streets one by one with the kids and with other older men and women, and shouting with all his might were rights that the Islamic Revolution had given him.

Mansour didn’t know the definition of “Islamic Revolution.” He only knew that the Islamic Revolution had raised him, had made him a man, and had entered him into the field. It had made a warrior out of him. Revolution was something that had given him the permission to talk; to state his thoughts, and to be unafraid of father’s anger and mother’s yells- although it was a long time that father wouldn’t get angry at him because of his big words, and mother wouldn’t yell at him.

Every night, when he got back home, he felt he had grown up more; bigger, wiser, more mature, and maybe more of a man! He felt like he had learned new things and had seen new things; new and strange things.

After his father left, Mansour shoved a piece of bread in his pocket, tied his shoelaces tightly, and left the house.

***

Ten or twelve of the kids had gathered at Delgosha Junction. When Mansour got there, he greeted them and stood beside them. Before the Islamic Revolution, he didn’t know any one of them except Javad, Akbar, and Mahdi, and he never talked to anyone except these three. But now it was as if he had been friends with all of them for years. There was passion, heat, and sorrow in the kind eyes of all of them. They all talked like each other and shouted like each other. They were like a thousand same-shaped candles. They burned and illuminated their life with this burning. It was just three days ago that one of the kids had been shot; but thank God, the bullet had hit his leg. The kids would go to see him all the time, kiss his father’s face, and congratulate his mother. They didn’t know why they should congratulate her, but they felt that the boy’s parents weren’t unhappy about the incident. They even felt a little proud and honoured.

Mansour had recently learned the name of the boy who was shot and would sometimes forget it, but names didn’t matter. It mattered that he liked the boy very much.

At the same time that Mansour got there, a few other kids also came from the other alleys and joined the group. Then they came and came until they were a hundred in number. They had a few rolled pictures of “Agha” and a few pieces of cardboard. They hadn’t properly learned the way of doing things and they didn’t look very organized.

They glued the pictures on the cardboard, raised them on sticks, and set off. The grown-ups were going to meet near Jaleh Square, but a few of them came to check on the kids and helped them get in line and get moving. Mansour knew that their lines would break up later on and they wouldn’t be able to find each other until late at night or until the next morning.

***

When the kids neared Jaleh Square and saw the big crowd, they felt more confident and their voices gradually raised louder and louder. The voice of each one of them was lost among all the cries; but without the cries of all the kids, the sound was heard much weaker.

Mansour tried to raise his voice as high as he could. Sometimes, he thought that his father, uncles, and cousins might probably hear his voice. Sometimes, he would see his father, uncles and a lot of other acquaintances in the middle of the crowd. He was happy to see them and even happier if they saw him.

Then the big crowd started off.

It was like the days of mourning but it wasn’t mourning time. It wasn’t a celebration either. There was neither happiness nor sorrow. There was anger and the Islamic Revolution. Here were people who were shouting with all their might, saying what they liked and what they disliked; what they wanted and what they didn’t want. Mansour liked this condition.

The crowd was moving toward Fouzieh Square, and you couldn’t see the end of the crowd no matter how much of it moved forward. People were coming out from everywhere. Mansour sank into the crowd and joined his voice with the others. Now he couldn’t hear his own voice anymore. He could only hear the voice of the people. He didn’t see himself; he only saw the people.

The slogans changed every once in a few minutes, but they all followed the same pattern. Sometimes they shouted this slogan, and sometimes that one, and then they would get back to the first slogan again.

Mansour shouted along with the others, “Down with the oppressive and traitor Shah! Down with…”

***

It was just four months ago that he, like many other children, was chosen for the Shah’s birthday ceremony on the October 26. Mansour was tall and slim and played on the school basketball team. But October 26 and dancing in the middle of the square had nothing to do with basketball.

Masur had said, “I have to ask my father for permission.”

The stranger who was sitting in the principal’s office had answered, “Your father himself has to ask us for permission.”

Mansour had replied with courage, “I have to ask my father if he has to ask you for permission or not.”

The stranger had said, “We’ll hit you and your father on the back of your necks! Don’t be so cheeky anymore. You must be proud that you are chosen for this ceremony…”

Mansour was heartbroken, but he hadn’t dared to say anything else. He was afraid they would make trouble for his father.

That night, he told his mother what had happened and his mother had replied, “It’s ok. You have no other choice. If you don’t go, they’ll make your father jobless.”

Mansour shouted louder, “We don’t want the Shah! We don’t want the Shah!”

***

They had taken him to Amjadiyeh every day for a whole month and had forced him to exercise. He had to bend, stand straight, sit, stand, take his right hand up, take his left hand up, turn, kneel, and do many other meaningless moves from morning till afternoon, morning till afternoon…

Mansour liked to exercise, but he didn’t like to be bullied.

One time, when he had gotten very tired and wanted to rest a little, they had hit him hard on the back of his neck and had sent him back in line with a kick.

- “You idiot! Get back in line! Hurry up!”

***

Mansour, shouted louder again, “Our enemy is the Shah! The enemy of our freedom is the Shah! Down with this Shah! Down with this Shah!” and he tried to move up. He tried to push his way through the crowd and move forward as far as he could.

***

On October 26, a thousand children, ten thousand children, all the same age as Mansour, maybe a bit younger or a bit older, had gathered in the big square. The children stood in organized arrangements and made various shapes. They are shaped into a flower, a tree, a tri-colour flag and a crown. They had even written a sentence with a very organized arrangement: “Long live the Shah and Shahbanu”! Then they wrote another sentence: “Long live the crown prince”!

Mansour told himself, “Long live my father who works twelve hours a day!”

Then they had shoved all the children into trucks like cattle and had returned them to the city and ditched them. Mansour’s mother would cry and say, “God damn them that they force these innocent children into doing anything they want.”

Father had said, “It’s ok. We’ll take revenge someday.”

On that horrible day, Mansour was forced to say “Long live the Shah” one hundred times.

- “It’s ok. We’ll take revenge someday. Father doesn’t say anything just like that…”

***

Mansour moved closer and closer. His body felt hot. He was sweating. The heat was coming out of his entire body. He moved a few steps up and shouted, “Shah! We will kill you! Shah, we will kill you!”

The neighbourhood kids weren’t around anymore. Mansour was opening his way forward from among the crowd, apart from all the kids; even apart from Akbar, Javad, and Mahdi. He thought the Shah was standing up there, in front of all the people and was seeing him. He thought he could look the Shah in the eyes and shout, “We will retaliate now! We will retaliate now!”

***

Another time, they had taken him for the crown prince’s birthday party. The crown prince was sitting high up, and was seen like an ant; he was watching everything with his binoculars. They had made Mansour and a thousand other children run around like dogs and had forced them to shout hurray.

Mansour had thought, “Can the crown prince who is as little as an ant from down here, see all of us? Can he tell from my face that I don’t like to shout for nothing?”

After the ceremony, they had come and said, “The dear and kind crown prince enjoyed the ceremony very much and ordered us to thank all the children on his behalf. Now, in honour of this kind and good crown prince, applaud and cheer hurray for five minutes!”

Another time too, when the Shah and Shahbanu were returning from their winter vacation, they had taken Mansour and all the school children to applaud and cheer hurray.

The weather was very cold that day. It was raining very hard. Mansour didn’t have proper undershirt and warm clothes. He didn’t have a hat either. While he was shivering and crying of knee pain, he was forced to shout “Long live the Shah! Long live the Shah!” One of the television reporters had seen him by chance and had told the cameraman to shoot him. They had turned the camera to Mansour’s face and the reporter had shouted, “What a strange sight! The children of our homeland are crying out of the joy of seeing their dear Shah and Shahbanu! These are tears of joy streaming down the face of this Shah-loving child! Yes…the joy of seeing the dear Shah and Shahbanu!”

Mansour wasn’t able to say “I haven’t even seen and don’t even want to see the Shah and Shahbanu. My knees are hurting. And they’re hurting a lot. I’m crying out of knee pain….” And the very fact that he wasn’t able to talk and say the truth out loud had upset him and angered him even more.

When he got back home that night, he had a throat ache and fell ill in bed for eight days.

His father had said, “What luck we have! They go skiing and having fun, my child has to tolerate the pain. It’s ok…one day we will retaliate all of this.”

Mansour had murmured, “One day, one day… that’s all I’ve heard for as long as I can remember…”

His father who was agitated and distressed, shouted, “Son! When I say we will take revenge someday, this means I might take revenge, or you might take revenge, or your children might take revenge… What matters is that we shouldn’t stop thinking about taking revenge…do you understand?”

Mansour had quietly said, “I understand.”

But he had thought, “What’s the use of my children taking revenge when I’m the one tolerating this throat ache and knee pain? The knee pain and throat ache is mine, revenge has to be mine too…”

They had taken Mansour along with the school children to welcome the Shah and Shahbanu three other times. Every time the Shah and Shahbanu returned from their trips to Europe, America and other places, Mansour and the other kids were forced to go and stand beside the road, scream, wave, throw flowers, and shout “Long live the Shah!”…

And each time, when Mansour got back home tired and helpless and dropped down in a corner, his father would murmur the same things he always said, “Alright! Things won’t stay this way. One day, we’ll shout so loudly that the world will tremble…

***

Now, Mansour was able to shout; he could shout so loud to shake the world. He could roar. He could tear his throat and say that he doesn’t like the Shah; that he doesn’t like the Shah’s children; that he doesn’t like the Shah’s guests. He doesn’t like to bully and be bullied around. And that, when someone talks about his father, he doesn’t like a nobody to say “We’ll hit your father on the back of his neck…”

Mansour was enraged. His whole being has turned into a piece of fire. He wanted to stand in front of all the people in any way he could, face to face with the Shah, and yell “Shah! We will kill you! Shah! We will kill you!”…

And eventually, he tried so hard, and put so much effort, and used so much energy until he saw himself ahead of the others – in the first row, beside the big men whose voices trembled the earth and the sky.

Mansour didn’t lose the spot he had acquired with so much effort. Right there, in the first row, he moved ahead shouting.

They hadn’t reached Fouzieh Square yet when all of a sudden, trucks full of soldiers turned into Shahnaaz Street and came toward the people.

For a second, the voices seemed to stop. It was as if there was silence, complete silence. It was as though the trucks were soundless too.

For only one second.

And then, the voices went up again. Mansour felt that the new voice was coming from his own throat. He thought he was the one who had shouted the first cry, but that second was so short that it wasn’t even counted.

Then, Mansour saw the soldiers who were pointing the machine guns toward the people from on top of their trucks. He had seen this sight before too; but he had never seen himself in front of a machine gun. One of the trucks was less than fifty steps away from him; less than fifty steps! He could clearly see the machine gun’s barrel and ammunition belt. He could even see the face of the soldier sitting behind the machine gun.

Oh…this was Javad Agha; Hoseyn Agha the shoemaker’s elder son. This man was from Mansour’s neighbourhood, from Mansour’s alley; he was Mansour’s next-door neighbour.

Mansour recalled that Hoseyn Agha – Javad Agha’s father – must be among the crowd himself.

Mansour thought, “So these are the neighbours who are fighting against each other. How bad! How sad! I want to fight against Shah, not against Javad Agha. And this is what Javad Agha himself wants too. He must be pretending to shoot. He won’s shoot…”

The sound of the people’s cries raised louder and they moved forward more swiftly.

Mansour couldn’t take his eyes off of Javad Agha anymore. He wanted to call him and say, “Javad Agha! It’s me. Don’t shoot, ok?”

But it was too late.

The sound of the machine guns went up into the air; the sound of the machine guns and the sound of the crowd.

Everything became a mess all of a sudden. The big crowd retreated, but Mansour still moved forward. He knew that if Javad Agha saw him, he would recognize him, and when he recognized him, he wouldn’t shoot. He wanted to smile at Javad Agha and see Javad Agha’s response. He wanted Javad Agha to wink at him and tell him that this shooting is not real. He wanted him to say that he will never shoot at his neighbours.

The barrel of Javad Agha’s machine gun was pointing right at Mansour’s chest when Mansour raised his hand and shouted, “Javad…”

But it was too late. Too late…

Mansour’s body was torn from the ground and dropped down. The boy was still looking at Javad Agha. He wanted Javad Agha to at least realize that he had shot Mansour. He wanted him to realize this and be ashamed of himself…

For one second, Mansour remembered the boy who had been shot and wounded. He remembered how much he liked him and how all of the neighbourhood kids liked him. Mansour thought he is lying down in bed and thousands and thousands of children have come to see him. The room is filled. The yard is filled. The alley and street are also filled with children who have come to see him.

And so many flowers! So many flowers!

All were bright, red carnations.

Mansour saw the children come up one by one, bend down, smile at him, kiss his father, and congratulate his mother. This thought brought a vague smile to Mansour’s lips; his last smile. And the story ended. But it was actually just the beginning of the story…

***

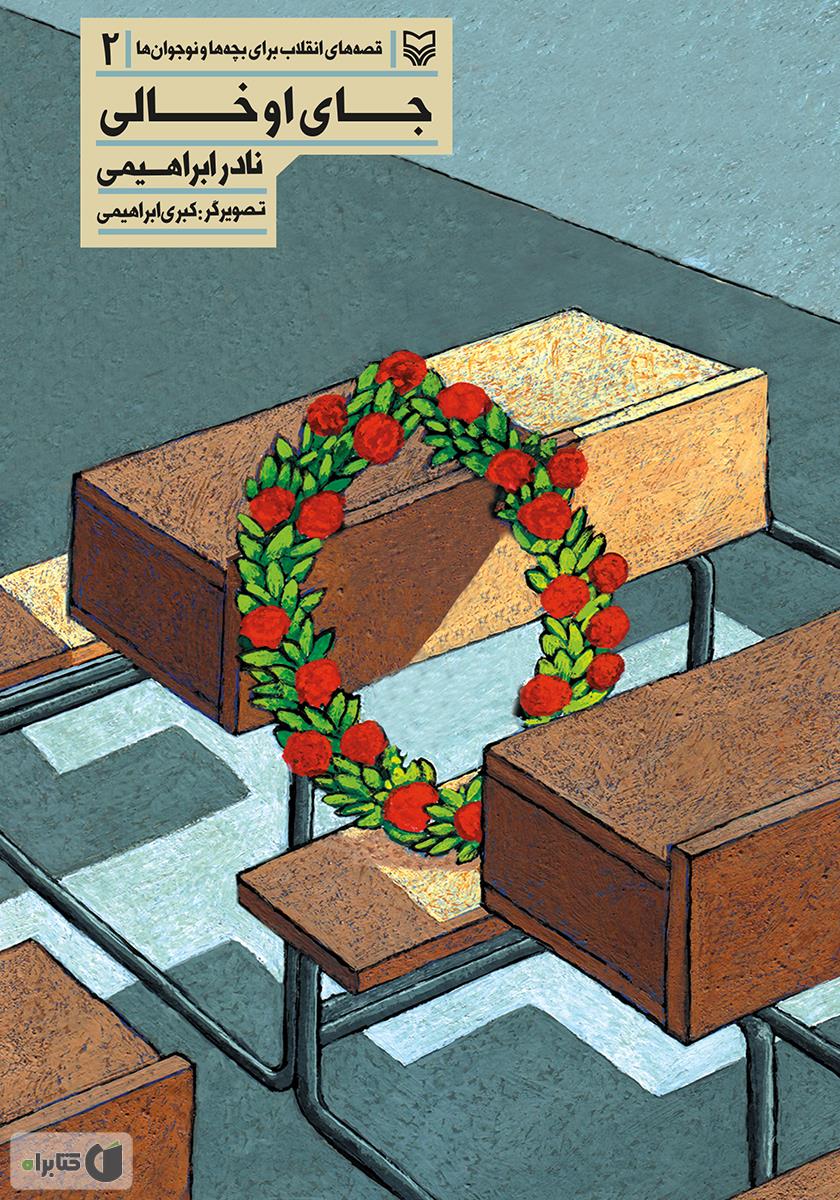

On the first day of school when the old teacher came to the classroom, he looked around and saw Mansour’s empty spot. Did I say Mansour’s empty spot? No, no, that isn’t right. He saw a garland of red carnations that the kids had placed on the bench, in Mansour’s spot. A big flower garland, a very big garland, as big as the entire class, as big as the entire school, as big as the entire nation…

The kids didn’t cry. They didn’t cry at all. It was only the old class teacher who suddenly burst into tears and cried out loud.

With a power that trembled the whole school, the whole Iran, and the whole world, the kids shouted together, “We will kill the Shah!”

***

We will kill the Shah!

We will kill the Shah!

It was like the days of mourning, but it wasn’t mourning time. It wasn’t a celebration either. There was neither happiness nor sorrow. There was anger and the Islamic Revolution. Now, the kids completely knew the definition of “Islamic Revolution” and shouted with all their might…

***

Revolutions are full of pain, and one of the worst and heaviest pains of the Islamic Revolution is the pain of children getting killed, but the happiness that is brought about for the people and especially for the children after each victorious Islamic Revolution is much greater than those pains…

The memory of Mansour and all other Mansours is honoured forever!

All of the red carnations of our homeland are a garland of flowers for them.

Stories of the Revolution for Children and Youths – 2

It was like the days of mourning, but it wasn’t mourning time. It wasn’t a celebration either. There was neither happiness nor sorrow. There was anger and the Islamic Revolution. Here were people who were shouting with all their might, saying what they liked and what they disliked; what they wanted and what they didn’t want. Mansour liked this condition.

Sureye Mehr Publication

Office of Literature on the Islamic Revolution

Archive of Culture and Art

leave your comments