Between 1960 and 1970, the Pahlavi regime embarked on extensive development projects. However, these projects ultimately led to an imbalance in the development of the economic and political spheres. Due to the oil revenues, the political power, along with the relative autonomy and independence of the government were consolidated. The regime thought that the monopolization of political power was the only possible way to compensate for the country’s all-encompassing backwardness and to modernize society. However, the methods employed to consolidate political power gradually led to the Pahlavi regime becoming an independent entity, isolated from society. Furthermore, central power and authority would direct the social and economic reforms that were shaped to fulfill the needs of this modern dictatory. The implementation of modernization policies greatly increased government intervention in capital accumulation, with oil revenues playing a major role in this regard.

Consequently, the development that occurred in Iran was a pseudo-modernization that was accelerated by oil revenues. The housing situation was terrible and disastrous, except for government beneficiaries and commercial entities. Most cities, including Tehran, lacked efficient sewage systems. Healthcare services were expensive, inapt and hazardous for the rich and poor.

Nevertheless, political and economic policies focused on the rapid expansion of small and large cities. The increase of the income of the urban population led to the decline of agriculture and rural settlements, resulting in mass migration from rural areas to cities. What also added to this migration, was the growth of government bureaucracy and the centralization of executive decisions.

The development policies pursued by the Pahlavi regime were mainly based on Western technology, which led to the decline of agriculture and a change in Iran’s economic and social structure. Government expenditure in the field of education increased in tandem with oil revenues and took priority over other social services. However, the program known as Sepah-e Danesh, which aimed at promoting literacy in rural areas, was fruitless. Nonetheless, it caused the government to spend excessively on a mere propaganda project. Moreover, some of the educated class treated the rural residents improperly, which provoked anger in the rural areas. Some of the program’s beneficiaries exploited their students and patients in various ways without being prosecuted. A significant portion of the education budget was allocated to urban areas, especially major cities, with the government offering some of its affiliated officers and personnel prominent political bribes to pursue their education. This had a considerable impact on the inflation rate.

By exploiting the oil resources, the multinational corporations exacerbated poverty and deprivation within society. Wealth remained predominantly in the hands of the upper class. This resulted in the Iranian economy becoming an example of the degradation of a national economy among Third World countries. A country that sought to reach Western growth and development standards through the relentless sale of oil.

In fact, the sudden and sharp increase in oil prices provided Iran’s economy with abundant financial resources in the 1970s. However, instead of seizing such a golden economic opportunity, the government focused its efforts on supporting the global financial system, doing so by investing in bankrupt American and European factories and companies, and purchasing weapons. A portion of the oil revenue was also spent on importing foreign products, including American wheat, Thai rice, Pakistani onions, Indian potatoes, South African oranges, Israeli eggs, as well as cheese and bananas. That said, these items could have been obtained in Iran by properly managing the agricultural industry. This lack of a clear economic policy, in addition to excessive spending, such as the holding of the 2500-year Imperial celebrations, and the inequitable distribution of national wealth ultimately caused the overexploitation of national resources and economic discrimination, leading to poverty and deprivation for a large part of the Iranian populace.

Due to the royal government's excessive spending, the increase in oil revenues gradually turned into inflation and created a wide gap between urban and rural incomes, uncontrolled migration, recession of the agricultural industry in rural areas, high unemployment rates in cities and income inequality in urban areas. It also created great disparity among social classes. Until the mid-1970s, 40 percent of the budget was allocated to 2 percent of the urban population. The poor in urban areas suffered from housing shortages, and 70 percent of their income had to be spent on rent. The low-income class bore the burden of inflation, unemployment, and the financial and economic corruption of the regime. Land reforms, ostensibly aimed at attracting the attention of rural residents and reducing the power and influence of large landowners, not only failed to diminish the power of the landowners, but also led to growing dissatisfaction within society and migration to cities. If the Pahlavi regime had focused more on agriculture instead of industry, rural-to-urban migration would have been much less, and the social problems of migrants would have been reduced. However, the land reforms mainly sought to create the necessary legitimacy for strengthening and expanding the Shah’s dictatorship, with economic goals playing a secondary role. The government, instead of effectively using the oil revenues and investing it in the agricultural sector, focused on increasing their military power in the region and neglected the social and economic problems and demands of the people.

Widespread rural-to-urban migration in the 1970s severely reduced the country’s food production, and the extensive import of food made the rural areas dependent on cities for food supplies, while they in turn were relying on foreigners in this regard. Migrants to cities faced insufficient employment opportunities, housing, and living conditions. They settled on the outskirts of cities and in impoverished neighborhoods. Those who left rural areas for cities encountered a very different culture, as most worked in construction which took place near expensive palaces and luxurious villas. In 1973, when oil revenues declined, the number of construction projects reduced, leading to a rise in unemployment. The backwardness, deprivation and dispersal of Iranians in small communities created harsh living conditions. The high rate of illiteracy and mortality among rural residents was a natural consequence of this situation. In 1974, only 13 percent of rural children had access to public education, while this figure reached 90 percent for their urban counterparts.

The policy of militarization and purchasing American weapons also had economic and social consequences, while further disrupting the natural order of Iranian society. Oil revenues were used to strengthen the military forces instead of being used to foster economic and social programs. The Shah, acting as the region’s policeman, spent huge sums of money on purchasing advanced military equipment.

Equally, sensitive and crucial occupations were monopolized by certain privileged groups, including the Bahais, the royalists, and their affiliates.

Therefore, the disregarding of religious values, indifference towards the demands of religious leaders, excessive liberty and lawlessness, the spread of obscenity and corruption, lack of regard for public decency, and the Bahais occupying key and sensitive administrative positions, together with their control of the economy, all contributed to increasing social discontent.

The Shah’s reforms caused him to become alienated from the three traditional influential bases of power, namely the merchants, the clergy, and the upper class of landowners. The Shah sought to support the lower class and conservative clergies, while the government wanted to prevent the clergy from promoting the teachings of Shia Islam. Therefore, the order to establish the Sepah-e Din was issued. Members of this organization were selected from graduates of religious studies from various universities and dispatched to different parts of the country. Sepah-e Din and similar religious propagators pursued three goals: 1. spreading a conservative and non-political version of Shia Islam that emphasized the compliance of the Islamic faith with monarchy, 2. gradually strengthening the cohesion between the Shia and the state, and 3. demonstrating the government’s commitment and loyalty to Shia Islam. However, the clergy raised important objections towards the promotion of a Western-oriented culture and the Shah’s support for a pre-Islam Iran.

The presence of thousands of Westerners in Iran, along with the construction of hundreds of cinemas showing vulgar Western films, and the existence of discos and liquor stores, all symbolized the prevalence of foreign culture, which, according to scholars, endangered Shia Islam.

Overall, holding the 2500-year celebrations, the issue of capitalism, favoring the elements affiliated with foreigners and sometimes preferring non-Muslim Iranians over Muslims, expansion of gambling houses, prostitution centers and liquor stores, and showing vulgar movies in cinemas and on television were part of the efforts the Pahlavi regime made to confront the promotion of the Islamic culture in the country. The expansion of gambling houses and liquor stores was in line with Mohammad Reza Shah’s policy of modernism, which was to acquaint the youth with Western culture. By holding massive celebrations, the Pahlavi regime sought to depict pre-Islamic Iran as progressive and advanced, and post-Islamic Iran as regressive and backward. Organizing the 2,500-year celebrations and changing the Persian Solar calendar to the Imperial one was part of this policy, and all official documents, government publications and school textbooks were required to use this new calendar. SAVAK took control of all student and professional associations, including trade unions. They also censored the media and suppressed all opposition political parties, even if they were legal. Despite all these efforts, SAVAK failed to completely eliminate groups opposed to the autocratic regime.

Taking advantage of the massive oil reserves, the Pahlavi regime used the Rastakhiz Party as a means to appease supporters of the monarchy, with the Shah stating that those ‘who were not with us, were against us’. This was a complete form of dictatorship, and the formation of the Rastakhiz Party aimed to suppress all opposition groups to the monarchy and create a unified and cohesive nation under the rule and authority of the Shah. The establishment of the Rastakhiz Party inevitably escalated the opposition campaigns against the Pahlavi regime, as its founding was equal to the acceptance of the government’s failure over the past decades.

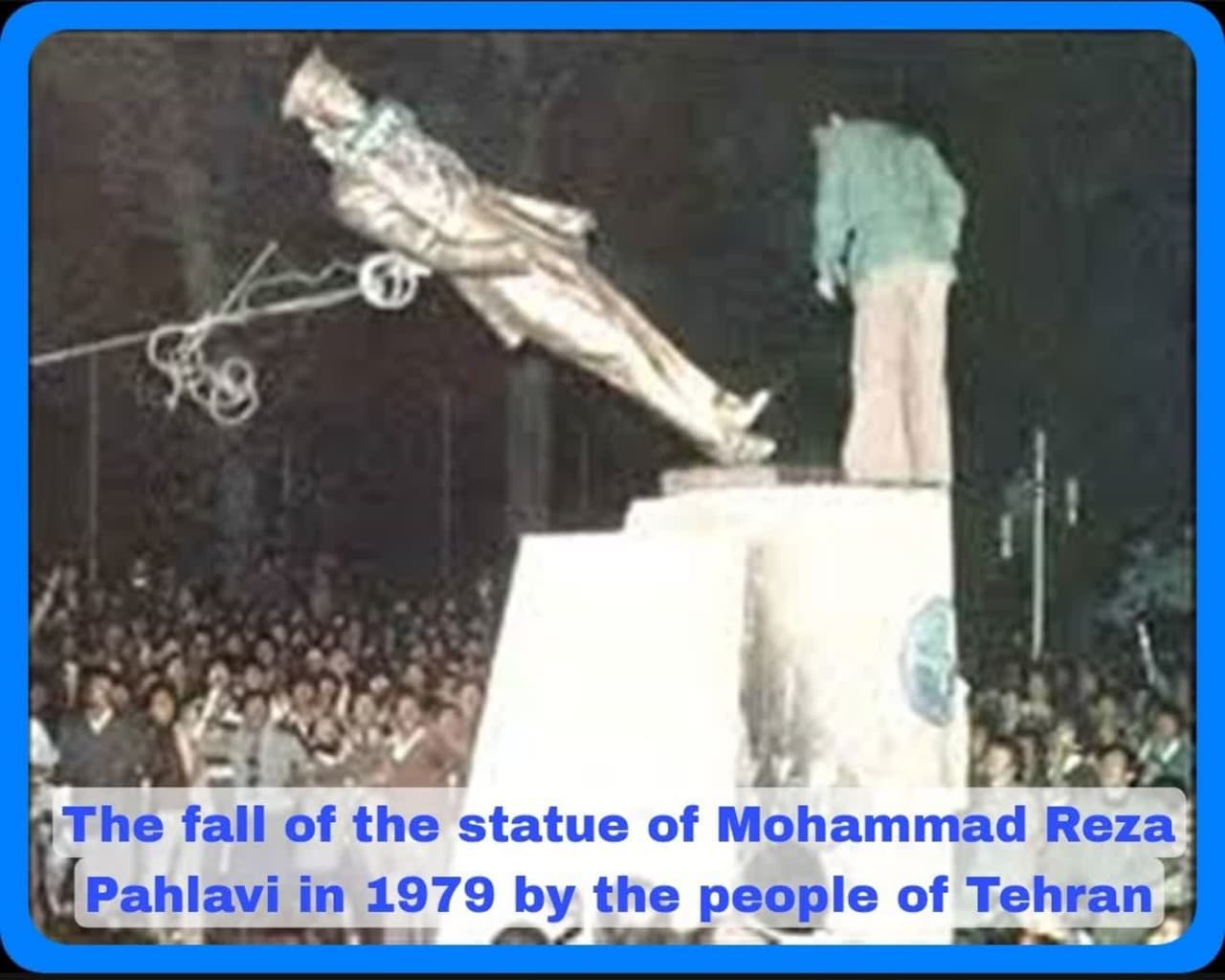

In summary, numerous factors, such as social discontent, financial and economic corruption, uncontrolled urban expansion due to rural-to-urban migration, employment of Bahais in key positions, lack of economic and infrastructure policies, the sizable presence of Americans in Iran, and others mentioned in this article, all contributed to provoking public discontent, which ultimately paved the way for the occurrence of the Islamic Revolution.

Archive of The History of the Islamic Revolution

leave your comments