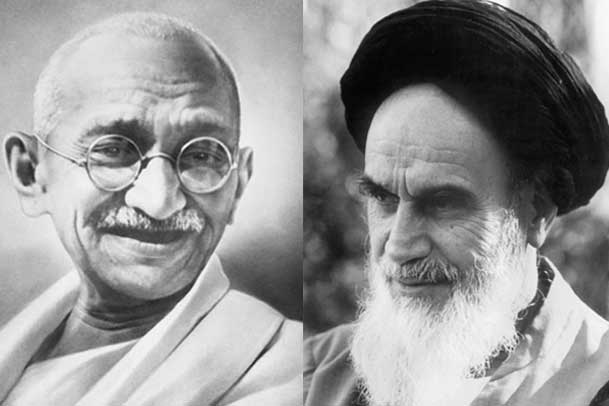

One of the ways to know more about the great political and religious figures is to compare their political life and especially their methods of fighting the enemy as well as their services to the country’s political modernization. When and under what conditions they emerged, against whom they fought, and why and how they did so, are some of the most important axes of this comparison. Two of these great figures were Imam Khomeini and Mahatma Gandhi. Despite some important differences between these two prominent personalities, there are many similarities between their political life and their contribution to the political modernization of Iran and India.

Imam Khomeini used two principles of “awaiting” and “martyrdom” that are part of the Shi’ah tradition to mobilize and unite the people against internal tyranny and foreign colonization. Gandhi also used the Indian traditions to fight against British colonialism and thereby redefined and reinterpreted the principle of “ahimsa” or “nonviolence.” For Gandhi, “nonviolence” and “the power of truth” have close ties so that practically it is impossible to separate them. They are like two sides of the same coin. However, for him, nonviolence is the means while the truth serves as the purpose. While he was searching for the truth, he discovered nonviolence. In Gandhi’s view, there is no other way than nonviolence to discover the truth. In other words, Gandhi believed that the goal of nonviolence is to establish the force of truth against injustice. This method was a kind of public defiance of laws that were seen as unfair and tyrannical in the view of Gandhi and his followers.

This civil opposition or the lack of cooperation, unlike the conventional method used in the West, is not taken place through direct confrontation, organizing the objections, and splitting the opponents so that one group would defeat another one, but for Gandhi, it should be based on compromise, not showing hatred towards the enemies and even being kind with them. This attitude was fueled by traditional Hindu beliefs regarding conflict management in politics and law, which focus on judgement and reconciliation within the community. For Imam Khomeini, too, “awaiting” and “martyrdom” or “the uprising in Karbala” are two important tactics for confronting aggression and oppression in any age and time. Awaiting creates hope and dynamism in the struggle of a Muslim while martyrdom prepares him for sacrifice and makes him not being afraid of death. As Gandhi’s principle of nonviolence is rooted in religion and tradition, Imam Khomeini’s preferred strategies (awaiting and martyrdom) also stem from religion and tradition and relate to the religious beliefs of Muslims regarding how to deal with injustice and tyranny. The most important common goal of Imam Khomeini and Gandhi was to fight against the aggressors, to remove the traces of fear and weakness in their followers, and to give them back the “courage and bravery.” Because colonial policies in India and Iran had destroyed the sense of cultural self-esteem and self-confidence among the people of the two countries, they were downgraded to humiliated, cowardly and disappointed people. Therefore, both Gandhi and Imam Khomeini realized that mobilizing and uniting the nation against the aggressors would occur by giving them courage and bravery. However, the two leaders’ perceptions of courage were somewhat different, though, in the end, for some reasons that will be explained, they became similar in practice.

For Gandhi, courage requires a certain kind of self-sacrifice and self-control. It stems from non-violence. Nonviolence is the peak of courage and bravery whereas violence is certainly a sign of fear. In Gandhi’s view, nonviolence is the result of inner struggle, not fear. Courage and bravery lie in the spiritual and inner strength, and not the physical and material powers. Bravery means upholding the rights by enduring personal suffering which is the opposite of armed confrontation and struggle. Courage means pure self-control and harming the self, resorting to the power of truth and not the physical force, the willing resistance of humans against the transgression instead of inability or the defeat of the will or submitting to destiny, the negative resistance and failure to cooperate without acting in retaliation and sacrificing the self not the others.

Explaining his nonviolent manner, Gandhi states that when I refuse to do something that my conscience refuses to accept, I use the spiritual force of God. He then says: “For example, the current government has enacted a law that includes me, but I don’t like it. If I, by using violence, force the government to abolish this law, I would use something which can be called the physical and material force. But if I do not comply with this law and accept the punishment of disobedience, I would use my spiritual power, which includes self-sacrifice. Hence, for Gandhi, if a person who is physically weak or incapable submits to running away from his opponent, it would be a sign of cowardliness. if he uses his power to confront his opponent and sacrifices his life in this way this would be bravery and courage but not nonviolence. Also, if he considers running away as a shame and maintains resistance and dies in his home without harming the enemy, this will be the very concept of resistance with nonviolence and bravery.

As much as Gandhi, and even more so, Imam Khomeini also emphasized courage and bravery. Like Gandhi, he believed that enduring suffering gives one courage and hence spiritual power. He also believed that one who fears God would fear nothing. Imam Khomeini, as the same as Gandhi, insisted that anyone weak in the fight against the enemy and preferred to flee or surrender, would be a coward. However, unlike Gandhi, Imam Khomeini limited courage to nonviolence. In his view, although nonviolence and forgiveness are better than violence, yet it is permissible to resort to violence in cases of coercion and urgency, provided that it is carried out for the sake of God and fulfilling the duty, and not to obey the egos. In other words, From Imam Khomeini, defending oneself against the enemy is rational and logical. It is because of this pure intention that, in Imam Khomeini’s ideology, the concept of war would go beyond the mere physical confrontation and turns into the “jihad” or “holy war.”

As such, Imam Khomeini’s conception of courage and bravery is neither entirely in line with Western attitudes (because, in their view, courage merely means showing off and physical victory over the enemy and therefore there is no room for the concepts of the intention, motivation, self-control and piety) nor with Gandhi’s attitude; yet, it is a combination of those two views, or more precisely, it is none of them. Although Imam Khomeini accepted the basis of Gandhi’s view that in confronting the enemy one should observe self-control, he believed that any attempt at doing so should not go beyond the limits of reason and logic. Loving the aggressor and forgiving him under all circumstances is absolute naivety and can result in irreparable damages. On this account, aggression, assertiveness, and even the use of force and violence are permissible and reasonable under certain circumstances. In a word, for Imam Khomeini, neither the bravery which stems from sheer nonviolence nor the sheer violence are acceptable, but acceptable bravery is a combination of both, albeit in normal circumstances nonviolence is given priority. In a word, nonviolence is the principle to which violence is the subordinate and exception.

Imam Khomeini’s practical methods in dealing with the aggressors confirm the above-mentioned view. In the fight against the Shah’s regime, his main emphasis, as the same as Gandhi, was on using peaceful strategies, and the negative approach rather than resorting to violence and weapons. By reviving the sense of identity and giving back the courage and confidence to Iranians, Imam Khomeini encouraged people only to march and protest, urging them most to disobey the governmental laws including asking soldiers to leave the garrisons and people to stop paying the taxes. However, he did not deny the use of military force and getting involved in a violent confrontation with the regime if necessary. The same was followed by Imam Khomeini after the victory of the Revolution of Iran, that is, the principle of nonviolence was the basis of his activities. Yet, in response to domestic and foreign plots such as the crisis in Kordestan or the Amol incident, and especially the imposing war against Iran by Iraq, Imam Khomeini was forced to order those who had been attacked to counteract against the attacks.

Although Gandhi and Imam Khomeini had different perceptions of bravery, Gandhi, as the same as Imam Khomeini, has also allowed the use of violence in some cases of which is “dastardliness”: “I consider using violence a thousand times better than making a nation and a race, dastard.” The other case is “cowardliness”: “When there is only one choice between cowardliness or violence, I recommend choosing force and violence.” That is why when Gandhi’s eldest son asked him if I were present in 1908 (when Gandhi had been attacked) what would be my duty? I should have run away and let you die or, with my physical power, defended you as much as I could? “Gandhi replied,” In such a case you have to defend me, even if it required using force and violence.

Adopting this attitude, Gandhi took part in the Boer War, Rolow Revolt [GS1] and World War I and advised those who believe in violent methods to learn how to use weapons. He even advised the Indians that they should resort to guns to defend their dignity so that they would not be humiliated or when he heard that as soon as the police invaded and robbed the homes and harassed the wives of the villagers who were living near Betia, they left their village on the pretext of following the principle of nonviolence, he shook his head to show a sense of embarrassment and reminded them that this is not the concept of nonviolence. Then he said, I expected them to stand up and defend those who are under their protection, and it would be very natural and courageous if they have defended their dignity and religion with the sword, and of course, it would be much nobler to confront the aggressors. The foregoing observations suggest that Gandhi’s nonviolent approach is changing the direction of violence instead of eliminating it, that is to say, it replaces the “physical violence” with “spiritual violence” which is silent though, like the physical violence, it is quite aggressive.

Thus, despite some differences in the two leaders’ perceptions of courage and bravery, in general, their strategy of struggle against the aggressors was very close and similar. Both leaders preferred a peaceful and political approach to the military and a nonviolent one. Both invited people to participate in protests, marches and demonstrations, using traditional beliefs as well as cultural and religious beliefs; both believed in mobilizing and uniting the people against the enemy through calling for disobedience, negative resistance, civil disobedience and the public strike; Both fiercely opposed cowardliness and treachery and condemned running away from dangers and disasters with the justification of defending the one’s family, relatives or friends; Both welcomed the death and called on their followers to do the same. However, Imam Khomeini, unlike Gandhi, did not consider the right of self-defence and counteraction in case of coercion and urgency and with pure intention to be a sign of fear and cowardliness, rather he viewed it as having the courage and acting rationally.

Archive of Imam Khomeini

leave your comments