Mohammad-Reza Pahlavi, Shah of Iran (October 26, 1919 – July 27, 1980), styled His Imperial Majesty and holding the imperial titles of Shahanshah (translated as King of Kings), and Aryamehr (sun of the Aryans), was the monarch of Iran from September 16, 1941, until the Iranian Revolution on February 11, 1979. He was the second monarch of the Pahlavi House and the last Shah of the Iranian monarchy.

Born in Tehran to Reza Pahlavi and his second wife, Taj al-Molouk, Mohammad-Reza was the eldest son of the first Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty, and the third of his eleven children. He was born with a twin sister, Ashraf Pahlavi. His father, a former Brigadier-General of the Persian Cossack Brigade, was of Mazandarani and Georgian origin.

On February 21, 1921, Reza Khan and the forces under his command together with Sayyed Zia’oddin Tabatabai staged a successful coup d’état against the reigning Qajar dynasty of Persia and took control of Tehran, and rule as Shah from 1925 to 1941. The Qajars’ excessive lifestyle had run up debts (mainly to Russia). Reza Shah had the support of General Edmund Ironside, the commander of the British troops in Iran. The aim was that British forces would have to leave Iran because of economic and political problems, and in their absence, a strong-armed force was needed to safeguard British interests and confront the Bolshevik Communists at home. This major event was later known as the “Black Coup.”

Reza Shah was crowned on April 26, 1926. At the ceremony, Mohammad-Reza, 7, was elected crown prince and his successor. The same year, the crown prince entered the Nezam Primary School, which was adjacent to the Golestan Palace, and completed his elementary education along with several other children of the courtiers. At the end of this period, in 1931, he was sent to Europe, along with several other adolescents and his dedicated physician and an Iranian instructor.

As a child, Mohammad-Reza Pahlavi attended the Institut Le Rosey in Lausanne, a Swiss boarding school, in 1932, completing his studies there in 1935. The Crown Prince was educated in French, and his time there left Mohammad-Reza with a lifelong love of all things French. In articles he wrote in French for the student newspaper in 1935 and 1936, Mohammad-Reza praised Le Rosey for broadening his mind and introducing him to European civilization.

Mohammad-Reza was the first Iranian prince in line for the throne to be sent abroad to attain a foreign education and remained there for the next four years before returning to obtain his high school diploma in Iran in 1936. After returning to the homeland, the Crown Prince, registered at the local military academy in Tehran where he remained enrolled until 1938, graduating as a Second Lieutenant. Upon graduating, Mohammad-Reza was soon promoted to the rank of Captain, a rank which he kept until he became Shah. During college, the young prince was appointed Inspector of the Army and spent three years travelling across the country, examining both civil and military installations.

Mohammad-Reza spoke English, French, and German fluently in addition to his native language Persian.

His first wife was Princess Fawziyah of Egypt (born November 5, 1921), a daughter of King Fuad I of Egypt; she also was a sister of King Farouk I of Egypt. They married in 1939 and divorced in 1945 (Egyptian divorce) and 1948 (Iranian divorce). Mohammad-Reza’s marriage to Fawziyah produced one child, a daughter, Princess Shahnaz Pahlavi (born 27 October 1940). Their wedlock was not a happy one. Mohammad-Reza’s dominating and extremely possessive mother saw her daughter-in-law as a rival to her son’s love and took to humiliating Princess Fawziyah, whose husband sided with his mother. A quiet, shy woman, Fawziyah described her marriage as miserable, feeling very much unwanted and unloved by the Pahlavi family and longing to go back to Egypt.

In the summer of 1941, Soviet and British diplomats passed on numerous messages warning that they regarded the presence of some Germans administering the Iranian state railroads as a threat, implying war if the Germans were not dismissed.

After a while, the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom, fearing that Reza Shah who pursued a policy of orientation towards the Germans during World War II, would cooperate with Nazi Germany to rid himself of their tutelage, occupied Iran and forced him into exile. Mohammad-Reza then replaced his father on the throne.

Much of the credit for orchestrating a smooth transition of power from the King to the Crown Prince was due to the efforts of Mohammad Ali Foroughi, an influential British contact and a top member of the Freemasonry.

On 16 September 1941, Prime Minister Foroughi and Foreign Minister Soheyli attended a special session of the parliament to announce the resignation of Reza Shah and that Mohammad-Reza was to replace him. The next day, at 4:30 pm, Mohammad-Reza took the oath of office and was received warmly by parliamentarians. The British would have liked to put a Qajar back on the throne, but the principal Qajar claimant to the throne was Prince Hamid Mirza, an officer in the Royal Navy who did not speak Persian, so the British had to accept Mohammad-Reza as Shah. The main Soviet interest in 1941 was to ensure political stability to guarantee Allied supplies, which meant accepting the throne.

The 37-year reign of Mohammad-Reza Shah was divided into two general lines. The first period was from September 1941 to the August 1953 coup, and the second period was from August 1953 to February 1979.

The beginning of the reign of Mohammad-Reza Shah faced quite a lot of turmoil. On the one hand, Iran was occupied by Soviet and British forces, and on the other hand, there were many problems such as famine, disease, and instability in the country. He did not have much power in the first period of his reign and did not directly interfere in the affairs of the country and was more likely to follow the advice of his courtiers and advisers.

The Shah was the target of two unsuccessful assassination attempts. On February 4, 1949, the Shah attended an annual ceremony to commemorate the founding of Tehran University. At the commemoration, Naser Fakhraraei, posing as a photographer and hiding the gun in the camera case, fired five bullets at the Shah at a range of ten feet. Only one of the shots hit the Shah and his cheek grazed. Fakhraraei was immediately killed by nearby officers. It then rumoured that Fakhraraei was a member of the Tudeh Party, which was subsequently outlawed by the parliament. The assassin was also suspected of being connected to the religious fundamentalist Fadaiyan-e Islam. The Shah says that support “for the crown surged” as a result of the failed assassination.

Anxious to blame the Communists, the Shah seized the opportunity to declare a conspiracy of religious and Communist radicals and decreed martial law. He also ordered an emergency session of the parliament, the same night he was shot. Through this session, he suppressed his political opposition, including what would prove an ineffective ban on the Tudeh Party. The Shah ordered the closure of newspapers critical of his policies, and for treasonous activities he had Tudeh Party leaders arrested. He also sent Ayatollah Kashani to exile — he had formed a strategic alliance with the Fadaiyan.

Following the assassination attempt, in an atmosphere of national sympathy for the monarchy, the Shah called for a Constituent Assembly to make amendments to the Constitution, to give him more power. He sought a royal prerogative giving him the right to dismiss the parliament, providing that new elections were held to form a new parliament. He also specified a method for future amendments to the Constitution. The amendments were made in May 1949 by the unanimous vote of the Iran Constituent Assembly.

On 27 February 1949, the parliament voted in support of the Shah’s bill calling for a Constituent Assembly to re-examine the Constitution of 1906. The Shah selected the Iran Constituent Assembly members from his supporters. To fill the Constituent Assembly, he chose men who were friendly to his wishes. While the men were preparing to meet, the Shah pushed through laws against newspaper criticism of the royal family, and laws that changed crown land holdings from general ownership to ownership under his name alone. He also increased his pressure for the formation of the Senate of Iran, an upper house of parliament that had been written into the Constitution in 1906 but never formed. The Senate was expected to favour the Shah.

Mohammad-Reza Shah’s second wife was Soraya Esfandiari (June 22, 1932 – October 26, 2001), the only daughter of Khalil Esfandiari, Iranian ambassador to the Federal Republic of Germany. During his life with the Shah, Soraya did not deal with political issues, focusing more on charity and public health care. They married in 1951 but divorced in 1958. Their wedlock suffered many pressures, particularly when it became clear that she was infertile. She rejected the Shah’s suggestion that he might take a second wife, as he rejected her suggestion that he might abdicate in favour of his half-brother. Being half-German half-Iranian Catholic, Soraya was mistrusted by Muslim clerics; she was also resented by the Shah’s possessive mother. In March 1958, the Shah wept as he announced their divorce. Soraya was said to be the Shah’s, only true love.

By the early 1950s, the political crisis brewing in Iran commanded the attention of British and American policy leaders. In 1951, Mohammad Mosaddeq was appointed prime minister. He was committed to nationalizing the Iranian petroleum industry controlled by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC). Under the leadership of Mosaddeq and his nationalist movement, the Iranian parliament unanimously voted to nationalize the oil industry—thus shutting out the immensely profitable AIOC, which was a pillar of the United Kingdom’s economy and provided it political clout in the region.

A month after the Shah’s second marriage, the Senate passed the National Petroleum Bill on March 20, and Iran’s political atmosphere entered a new phase, the “nationalization of the oil industry.”

Within Mosaddeq’s premiership, the Shah had the least power under the constitution. In her memoirs, Soraya writes:

“The Shah found himself under pretty difficult circumstances. He would go to his office as a daily routine and return, but it was only an official aspect. His ministers would no longer care for him.”

At the beginning of his second year in office, Dr. Mosaddeq urged the Shah to delegate the authority of the Ministry of War to him. The Shah’s opposition to this demand led to the resignation of Mosaddeq and the appointment of Ahmad Qavam (July 16-21, 1952). But with the uprising of the people on July 21, the Shah was forced to step down and re-appoint Mosaddeq as prime minister.

The struggle between the Shah and Mosaddeq continued during Dr. Mosaddeq’s second term in office. The Shah finally, in August 1953, with the approval and support of the United States and the United Kingdom, signed the decree on the removal of Mosaddeq and the appointment of Lieutenant General Fazlollah Zahedi to the post of Prime Minister and then went to Ramsar (the capital of Ramsar County, Mazandaran Province, lies on the coast of the Caspian Sea) with Soraya.

Before the first attempted coup, the American Embassy in Tehran reported that Mosaddeq’s popular support remained robust.

The Communists staged massive demonstrations to hijack Mosaddeq’s initiatives, and the United States actively plotted against him. On 16 August 1953, the right-wing of the Army attacked. A coalition of mobs and retired officers close to the Palace executed this coup d’état. Despite the high-level coordination and planning, the coup initially failed, causing the Shah to flee to Baghdad, and then to Rome.

During the following two days, the Communists turned against Mosaddeq. The opposition grew tremendously against him. They roamed Tehran, raising red flags and pulling down statues of Reza Shah. This move was rejected by conservative clerics like Kashani and National Front leaders like Hoseyn Makki, who sided with the Shah. On 18 August 1953, Mosaddeq defended the government against this new attack. Tudeh partisans were clubbed and dispersed.

The Tudeh Party had no choice but to accept defeat. In the meantime, according to the CIA plot, Zahedi appealed to the military, claimed to be the legitimate prime minister and charged Mosaddeq with staging a coup by ignoring the Shah’s decree. Zahedi’s son Ardeshir acted as the contact between the CIA and his father. On 19 August 1953, pro-Shah partisans – bribed with $100,000 in CIA funds – finally appeared and marched out of south Tehran into the city centre, where others joined in. Gangs with clubs, knives, and rocks controlled the streets, overturning Tudeh trucks and beating up anti-Shah activists. As Roosevelt was congratulating Zahedi in the basement of his hiding place, the new Prime Minister’s mobs burst in and carried him upstairs on their shoulders. That evening, Henderson suggested to Ardeshir that Mosaddeq not be harmed. United States actions further solidified sentiments that the West was a meddlesome influence in Iranian politics.

Mohammad-Reza returned to power, but never extended the elite status of the court to the technocrats and intellectuals who emerged from Iranian and Western universities. His system irritated the new classes, for they barred from partaking in real power. Indeed, the second period of the Shah’s reign, which lasted 25 years, was his tendency toward individual rule and ignoring the principles and freedoms outlined in the constitution.

The Shah founded the SAVAK in 1957 with United States assistance to counteract the anti-monarchy movements. The organization was later strengthened with the help of Mossad. SAVAK played the role of repressing the opposition and stabilizing security for the Pahlavi government.

In 1959, Mohammad-Reza Pahlavi married his third and final wife, Farah Diba (born October 14, 1938). The couple remained together for twenty years until the Shah’s death. Farah Diba bore him four children: Reza Pahlavi (born October 31, 1960), Farahnaz Pahlavi (born March 12, 1963), Alireza Pahlavi (born April 28, 1966), Leyla Pahlavi (March 27, 1970–June 10, 2001).

In 1961, under the United States pressure to reform Iran, he appointed Ali Amini as prime minister. But because of his long-standing fear of the Prime Minister’s power in the monarchy, he travelled to the United States and met with President John F. Kennedy at the time to undertake reforms.

Shortly after coming back from the United States, the Shah ousted Amini and replaced a long-time loyal friend, Amir-Asadollah Alam. The Shah submitted his reform plan known as the “White Revolution” on six main principles to a public referendum on January 26, 1963, including land reform, electoral reform (women’s suffrage), profit-sharing for workers, and so forth. At this time, the Shiite clergy led by Ayatollah Khomeini opposed the Shah’s White Revolution. In his speeches, Khomeini argued that the implementation of these principles was primarily intended to consolidate the Shah’s absolute reign, not the welfare of the people, “At a time when our men do not have full rights and freedom of vote, declaring women’s suffrage is nothing else than deceit and hollow propaganda.” The protests culminated with the arrest of Khomeini and the bloody uprising of 6 June 1963 and were suppressed by Alam’s direct order.

In March 1964, Hasan Ali Mansour’s government replaced the Alam government. Mansour set free Khomeini as an agreeable act for the clergy, but then faced strong opposition from Khomeini because of the Capitulation bill (The Immunity of United States Military Advisors in Iran) submitted to the parliament at the time of his ministry. Khomeini was arrested and sent into exile.

Mansour was assassinated on the anniversary of the White Revolution referendum and succeeded by Amir-Abbas Hoveyda, who was the Minister of Finance in Mansour’s cabinet.

The second attempt on the Shah’s life occurred on 10 April 1965. One of the Immortal Guard soldiers shot his way through the Marble Palace. The assassin was killed before he reached the royal quarters, but two civilian guards died protecting the Shah.

Following the incident, the Constituent Assembly re-formed, and Farah, the wife of the Shah, became the regent under the new law, as Reza Pahlavi spent his childhood, and he would not have been able to succeed his father if something had happened to the Shah. By this change, the Shah was crowned as emperor on 26 October 1967, and Farah became Shahbanu (Empress) of Iran, a title created especially for her—previous royal consorts had known as Malakeh (Queen).

The fourth decade of the Shah’s reign begins with celebrations marking the 2500th anniversary of the Royal Monarchy. The festival intended to demonstrate Iran’s long history and to showcase its contemporary advancements under Mohammad-Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran. The sumptuous feast made Iran the world’s most newsworthy country for a week.

In Persepolis, near the tomb of Cyrus I, the Shah planned to celebrate the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire, for three days, from 12 to 14 October 1971. It would be “the biggest party on earth,” announced the Shah. The message was further reinforced the next day when the “Parade of Persian History” performed when 6,000 soldiers dressed in the uniforms of every dynasty from the Achaemenids to the Pahlavis marched past Mohammad-Reza in a grand parade so that many contemporaries remarked, “surpassed in the sheer spectacle the most florid celluloid imaginations of Hollywood epics.” During the extravagant festivities, the Shah was quoted as saying at Cyrus’s tomb:

“Rest in peace, Cyrus, for we are awake.”

On the final day, the Shah inaugurated the Shahyad Tower (later renamed the Azadi Tower after the Iranian Revolution) in Tehran to commemorate the event. The tower was also home to the Museum of Persian History. In it was displayed the Cyrus Cylinder, which the Shah promoted as “the first human rights charter in history.” A brochure put up by the Celebration Committee explicitly stated the message:

“Only when change is extremely rapid, and the past ten years have proved to be so, does the past attain new and unsuspected values worth cultivating,” going on to say the celebrations held because “Iran has begun to feel confident of its modernization.”

All the supplies and services of these extremely costly celebrations, without exception, were brought from abroad, especially France, while people of villages across Iran, were grappling with starvation and the deaths of their livestock. That led to several European television channels besides broadcasting festive footage, showing scenes of the deplorable conditions of the Iranian people’s lives, especially the slum dwellers.

After the 2,500-year anniversary celebrations, two issues led the Shah to fully consolidate the foundations of his autocracy. Firstly, Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to Tehran; Nixon allowed the Shah to buy any military weapon (except for nuclear weapons) from the United States. In the second place, the sudden rise in oil prices (quadrupled) in world markets; the change caused by the Arab-Israeli war, dramatically increased Iran’s oil revenues. From then on, the Shah spent a large amount of the country’s budget to buy military weapons from the United States and Europe.

With Iran’s great oil wealth, the Shah became the preeminent leader of the Middle East and self-styled “Gendarme” of the Persian Gulf. He even sent troops to Oman to suppress the communist guerrilla movement and, in fact, to safeguard United States interests in the Middle East.

The Shah was spreading his despotic way of governing the country day by day. He intervened in all government affairs without regard to the constitution. One by one, the ministers of Hoveyda’s cabinet, without consulting, had individual meetings with His Majesty. Besides, the Shah did not allow anyone to interfere or comment on the three issues— the army, foreign policy, and oil.

The Shah’s diplomatic foundation was the United States’ guarantee that it would protect his regime, enabling him to stand up to larger enemies. While the arrangement did not preclude other partnerships and treaties, it helped to provide a somewhat stable environment in which Mohammad-Reza could implement his reforms. Another factor guiding Mohammad-Reza in his foreign policy was his wish for financial stability, which required strong diplomatic ties. A third factor was his wish to present Iran as a prosperous and powerful nation; this fuelled his domestic policy of Westernization and reform. A final component was his promise that communism could be halted at Iran’s border if his monarchy was preserved. By 1977, the country’s treasury, the Shah’s autocracy, and his strategic alliances seemed to form a protective layer around Iran.

It should be noted that during this period the Shah’s government took steps to implement welfare policies at the public level, including free school-to-university education, new social insurance, and free school nutrition, all of which were not with full success.

During the last years of his regime, the Shah’s government became more autocratic. In the words of an American Embassy dispatch:

“The Shah’s picture is everywhere. The beginning of all film showings in public theatres presents the Shah in various regal poses accompanied by the strains of the National Anthem..., The monarch also actively extends his influence to all phases of social affairs ..., there is hardly any activity or vocation in which the Shah or members of his family or his closest friends do not have a direct or at least a symbolic involvement. In the past, he had claimed to take a two-party system seriously and declared, ‘If I were a dictator rather than a constitutional monarch, then I might be tempted to sponsor a single dominant party such as Hitler organized.’”

As the life of the Shah’s monarchy increased, so did his totalitarianism. In the last years of the kingdom, no one dared to tell the Shah what was really going on in the country. If he had been said, he would have had a harsh reaction. The peak of the Shah’s autocracy and self-rule can be detected during the establishment of the Rastakhiz Party.

By 1975, Mohammad-Reza had abolished the two-party system of government in favour of a one-party state under the Rastakhiz (Resurrection) Party. This was the merger of the New Iran Party, a centre-right party, and a liberal party. The Shah justified his actions by declaring:

“We must straighten out Iranians’ ranks. To do so, we divide them into two categories: those who believe in Monarchy, the Constitution and the White Revolution and those who don’t ... A person who does not enter the new political party and does not believe in the three cardinal principles will have only two choices. He is either an individual who belongs to an illegal organization or is related to the outlawed Tudeh Party or in other words a traitor. Such an individual belongs to an Iranian prison, or if he desires he can leave the country tomorrow, without even paying exit fees; he can go anywhere he likes, because he is not Iranian, he has no nation, and his activities are illegal and punishable according to the law.”

Furthermore, the Shah had decreed that all Iranian citizens and the few remaining political parties become part of Rastakhiz.

From 1973 onward, Mohammad-Reza had proclaimed his aim as that of the “Great Civilization,” a turning point not only in Iran’s history but also the history of the entire world, a claim that was taken seriously for a time in the West.

Courtiers at the Imperial court were devoted to stroking the Shah’s ego, competing to be the most sycophantic, with Mohammad-Reza being regularly assured he was a greater leader than his much-admired General de Gaulle, that democracy was doomed, and that based on Rockefeller’s speech, that the American people wanted Mohammad-Reza to be their leader, as well as doing such a great job as Shah of Iran. All of this praise boosted Mohammad-Reza’s ego, and he went from being a merely narcissistic man to a megalomaniac, believing himself a man chosen by God Himself to transform Iran and create the Great Civilization. When one of the Shah’s courtiers suggested launching a campaign to award him the Nobel Peace Prize, he wrote on the margin:

“If they beg us, we might accept. They give the Nobel prize to any kakasiyah [black-face buffoon] these days. Why should we belittle ourselves with this?”

Befitting all this attention and praise, Mohammad-Reza started to make increasingly outlandish claims for the “Great Civilization,” telling a famous Egyptian journalist in a 1976 interview:

“I want the standard of living in Iran in ten years’ time to be exactly on a level with that in Europe today. In twenty years’ time, we shall be ahead of the United States.”

Reflecting his need to have Iran seen as “part of the world” (by which Mohammad-Reza meant the western world), all through the 1970s he sponsored conferences in Iran at his expense. He also sought to hold the 1984 Summer Olympics in Tehran. For most ordinary Iranians, struggling with inflation, poverty, air pollution, and the backwardness of the educational system, the Shah’s sponsorship of international conferences was just a waste of money and time.

By the end of 1977, the Shah had the support of a large number of politicians, especially the Republican Party. But that year, Jimmy Carter of the Democratic Party won the United States presidential election with a slogan of human rights protection. His administration prompted the Shah to implement a free political atmosphere program inside the country, regarding the question of human rights in Iran. But the opening up of the country’s political atmosphere could not go according to the Shah’s wishes.

The overthrow of the Shah came as a surprise to almost all observers. The first militant anti-Shah demonstrations of a few hundred started in October 1977, after the death of Ayatollah Khomeini’s son Mostafa. On 7 January 1978, an article was published in the newspaper Ettela’at attacking Sayyed Ruhollah Khomeini, who was in exile in Iraq at the time; Khomeini’s supporters had brought in audiotapes of his sermons, and Mohammad-Reza was angry with one sermon, alleging corruption on his part, and decided to hit back with the article, despite the feeling at the court, SAVAK and Ettela’at editors that the article was an unnecessary provocation that was going to cause trouble. The next day, protests against the article began in the holy city of Qom, a traditional centre of opposition to the House of Pahlavi.

Mohammad-Reza was diagnosed with cancer in 1974. As it worsened, from the spring of 1978, he stopped appearing in public, with the official explanation being that he was suffering from a “persistent cold.” In May 1978, the Shah suddenly cancelled a long-planned trip to Hungary and Bulgaria and disappeared from view. He spent the entire summer of 1978 at his Caspian Sea resort, where two of France’s most prominent doctors treated his cancer.

As nationwide protests and strikes swept Iran, the court found it impossible to get decisions from Mohammad-Reza, as he became utterly passive and indecisive, content to spend hours listlessly staring into space as he rested by the Caspian Sea while the revolution raged. The seclusion of the Shah, who normally loved the limelight, sparked all sorts of rumours about the state of his health and damaged the imperial mystique, as the man who had been presented as a god-like ruler was revealed to be fallible.

The Shah-centred command structure of the Iranian military and the lack of training to confront civil unrest were marked by disaster and bloodshed. There were several instances where army units had opened fire, the most notorious one being the events of 8 September 1978. On this day, which later became known as “Black Friday,” thousands had gathered in Tehran’s Jaleh Square for a religious demonstration. With people refusing to recognize martial law, the soldiers opened fire, killing and seriously injuring a large number of people. Black Friday played a crucial role in further radicalizing the protest movement. The massacre so reduced the chance for reconciliation that Black Friday is referred to as “the point of no return” for the revolution.

The Shah changed three prime ministers from September 1978 to January 1979, but none managed to contain the tide of the revolution. Arriving at a political impasse at this time, he was constantly meeting with the American and British ambassadors, seeking ways to quell the revolutionary movement of the people.

By October 1978, strikes were paralyzing the country, and in early December a “total of 6 to 9 million”—more than 10% of the country—marched against the Shah throughout Iran. In October 1978, after flying over a huge demonstration in Tehran in his helicopter, Mohammad-Reza accused the British ambassador Sir Anthony Parsons and the American ambassador William H. Sullivan of organizing the demonstrations, screaming that he was being “betrayed” by the United Kingdom and the United States. The Shah’s view of the revolution as a gigantic conspiracy organized by foreign powers suggested that there was nothing wrong with Iran, and the millions of people demonstrating against him were just dupes being used by foreigners, a viewpoint that did not encourage concessions and reforms until it was too late.

The revolution had attracted support from a broad coalition ranging from secular, left-wing nationalists to Islamists on the right, and Khomeini, who was now based in Paris after being expelled from Iraq, chose to present himself as a moderate able to bring together all the different factions leading the revolution.

On 5 November 1978, Mohammad-Reza went on Iranian television to say “I have heard the voice of your revolution” and promise major reforms. In a major concession to the opposition, on 7 November 1978, Mohammad-Reza freed all political prisoners while ordering the arrest of the former Prime Minister Amir Abbas Hoveyda and several senior officials of his regime, a move that both emboldened his opponents and demoralized his supporters.

On 21 November 1978, the Treasury Secretary of the United States Michael Blumenthal visited Tehran to meet The Shah and reported back to President Carter, “This man is a ghost,” as by now the ravages of his cancer could no longer be concealed. In late December 1978, the Shah found that many of his generals were making overtures to the revolutionary leaders and the loyalty of the military could no longer be counted upon. In a sign of desperation, the following month Mohammad-Reza reached out to the National Front, asking if one of their leaders would be willing to become prime minister.

On 16 January 1979, Mohammad-Reza left Iran at Prime Minister Bakhtiar’s suggestion, who sought to calm the situation. Before the Shah, most of the royal family and his statesmen and supporters had fled the country, taking the Iranian people’s funds with them. Spontaneous attacks by members of the public on statues of the Pahlavis followed, and “within hours, almost every sign of the Pahlavi dynasty” was destroyed. Bakhtiar dissolved SAVAK, freed all political prisoners, and allowed Ayatollah Khomeini to return to Iran after years in exile. In February, pro-Khomeini revolutionary guerrilla and rebel soldiers gained the upper hand in street fighting, and the military announced its neutrality. On the evening of 11 February, the dissolution of the monarchy was complete.

The worst part in the course of Mohammad-Reza Shah’s lifetime was the last year and a half of his life when spent in exile and wandering.

During his second exile, Mohammad-Reza travelled from country to country seeking what he hoped would be a temporary residence. First, he flew to Aswan, Egypt, where he received a warm and gracious welcome from President Anwar al-Sadat. He later lived in Morocco as a guest of King Hasan II. Mohammad-Reza loved to support royalty during his time as Shah and one of those who benefitted had been Hasan, who received an interest-free loan of $110 million from his friend. Mohammad-Reza expected Hasan to return the favour, but he soon learned Hasan had other motives. After leaving Morocco, Mohammad-Reza lived in Paradise Island, in the Bahamas, and Cuernavaca, Mexico, near Mexico City, as a guest of José López Portillo.

The Shah suffered from gallstones that would require prompt surgery. He was offered treatment in Switzerland but insisted on treatment in the United States. President Carter did not wish to admit Mohammad-Reza to the United States but came under pressure from many quarters, with Henry Kissinger phoning Carter to say he would not endorse the SALT II treaty that Carter had just signed with the Soviet Union unless the former Shah was allowed into the United States, reportedly prompting Carter more than once to hang up his phone in rage in the Oval Office and shout “Fuck the Shah!” Mohammad-Reza had decided not to tell his Mexican doctors he had cancer, and the Mexican doctors had misdiagnosed his illness as malaria, giving him a regime of anti-malarial drugs that did nothing to treat his cancer, which caused his health to go into rapid decline as he lost 30 pounds. In September 1979, a doctor sent by David Rockefeller reported to the State Department that Mohammad-Reza needed to come to the United States for medical treatment. The State Department warned Carter not to admit the former Shah into the United States, saying it was likely that the Iranian regime would seize the American embassy in Tehran if that occurred.

On 22 October 1979, President Jimmy Carter reluctantly allowed the Shah into the United States to undergo surgical treatment at the New York Hospital–Cornell Medical Centre. It was anticipated that his stay in the United States would be short; however, surgical complications ensued, which required six weeks of confinement in the hospital before he recovered. His prolonged stay in the United States was extremely unpopular with the revolutionary movement in Iran, which still resented the United States’ overthrow of Prime Minister Mosaddeq and the years of support for the Shah’s rule. The Iranian government demanded his return to Iran, but he stayed in the hospital. Mohammad-Reza’s time in New York was highly uncomfortable; he was under a heavy security detail as every day, Iranian students studying in the United States gathered outside his hospital to shout “Death to the Shah!,” a chorus that Mohammad-Reza heard. Mohammad-Reza could no longer walk by this time, and for security reasons had to be moved in his wheelchair under the cover of darkness when he went to the hospital while covered in a blanket, as the chances of his assassination were too great.

There are claims that Mohammad-Reza’s admission to the United States resulted in the storming of the United States Embassy in Tehran and the kidnapping of American diplomats, military personnel, and intelligence officers, which soon became known as the Iran hostage crisis. In the Shah’s memoir, Answer to History, he claimed that the United States never provided him with any kind of health care and asked him to leave the country. From the time of the storming of the American embassy in Tehran and the taking of the embassy staff as hostages, Mohammad-Reza’s presence in the United States was viewed by the Carter administration as a stumbling block to the release of the hostages, and obviously, he was, in effect, expelled from the country.

Mohammad-Reza wanted to go back to Mexico, saying he had pleasant memories of Cuernavaca but was refused. He left the United States on 15 December 1979 and lived for a short time in the Isla Contadora in Panama. This caused riots by Panamanians who objected to the Shah being in their country. General Omar Torrijos, the dictator of Panama kept Mohammad-Reza as a virtual prisoner at the Paitilla Medical Centre, a hospital condemned by the former Shah’s American doctors as “an inadequate and poorly staffed hospital,” and in order to hasten his death allowed only Panamanian doctors to treat his cancer. General Torrijos, a populist left-winger had only taken in Mohammad-Reza under heavy American pressure, and he made no secret of his dislike of Mohammad-Reza, whom he called after meeting him “the saddest man he had ever met.” When he first met Mohammad-Reza, Torrijos taunted him by telling him “it must be hard to fall off the Peacock Throne into Contadora” and called him a “chupon,” a Spanish term meaning an orange that has all the juice squeezed out of it, which is slang for someone who is finished.

The new government in Iran still demanded his and his wife’s immediate extradition to Tehran. A short time after Mohammad-Reza’s arrival in Panama, an Iranian ambassador was dispatched to the Central American nation carrying a 450-p. extradition request. That official appeal alarmed both the Shah and his advisors. Whether the Panamanian government would have complied is a matter of speculation amongst historians.

Fearing for his life, the Shah left Panama delaying further surgery. He fled to Cairo, Egypt, with his condition worsening. Anyway, the Shah again sought the support of Egyptian president Anwar al-Sadat, who renewed his offer of permanent asylum in Egypt to the ailing monarch. He returned to Egypt in March 1980, where he received urgent medical treatment. On 28 March 1980, Mohammad-Reza’s French and American doctors finally performed an operation meant to have been performed in the fall of 1979, then it turned out that “Cancer had reached the liver. The Shah would soon die ... The tragedy is that a man who should have had the best and easiest medical care had, in many respects, the worst.”

Ultimately, the Shah died on 27 July 1980 at age 60. He kept a bag of Iran soil under his death bed. Egyptian President Sadat gave the Shah a state funeral.

Mohammad-Reza is buried in the al-Rifa’i Mosque in Cairo, a mosque of great symbolic importance.

At a glance we can summarize the factors behind Mohammad-Reza Shah’s fall from power:

- The authoritarianism and selfishness of the Shah, especially from his mid-reign, would not allow anyone to criticize him. He acted in his own way in all affairs of the country.

- The spread of corruption in various forms of society, especially corruption in courtiers and their dependents and government officials, created a deep gap in society.

- Cultural and social policies of the Pahlavi government and disregard for the dominant culture of the Iranian people, especially the anti-religious policies of the Pahlavi government and its widespread propaganda in universities and schools, cinema, radio and television, and in the general public.

- Increasing the suppression of the opposition and creating an environment of terror in society by SAVAK.

- Expansion of influence and presence of foreign advisers in the pillars of the Pahlavi government humiliated the Iranian people.

Mohammad-Reza Pahlavi published several books in the course of his kingship and two later works after his downfall, include: Mission for My Country (1960), The White Revolution (1967), Toward the Great Civilization (1977), Answer to History (1980).

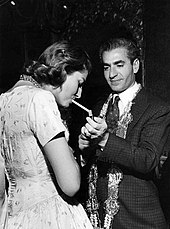

The Shah lighting a cigarette for his wife Soraya, 1950s

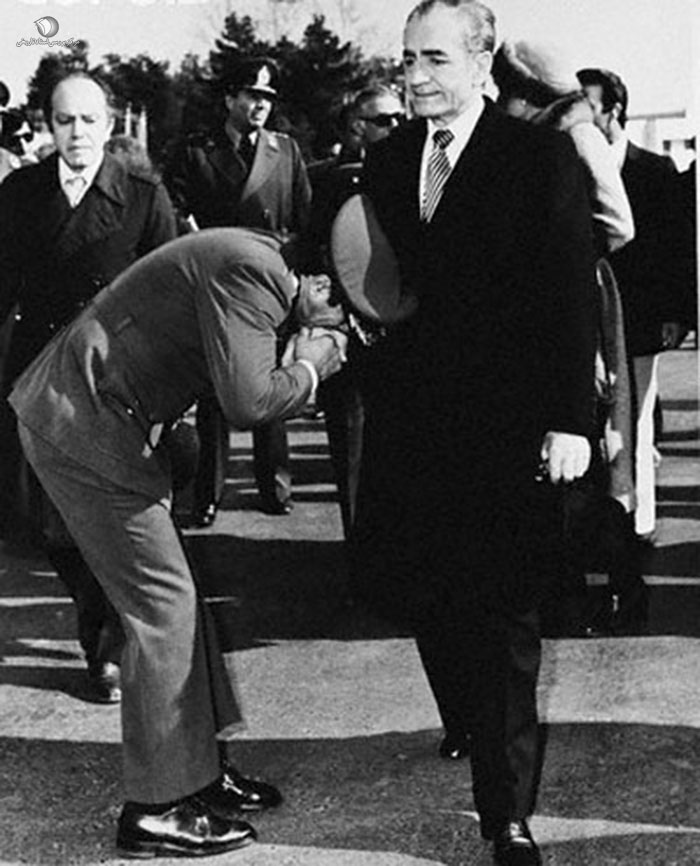

The Shah while fleeing Iran at Mehrabad airport

Supporters of the revolution remove a statue of the Shah in Tehran University, 1978

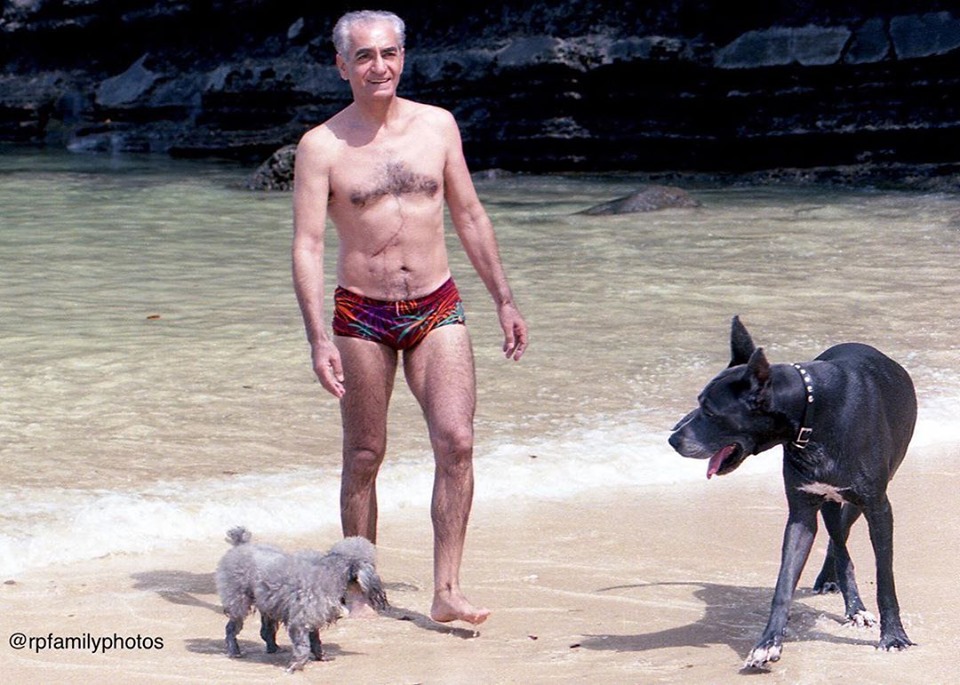

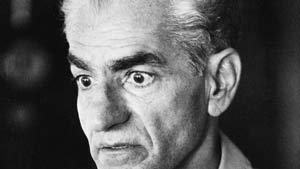

The Shah at the end

Archive of The History of the Islamic Revolution

leave your comments