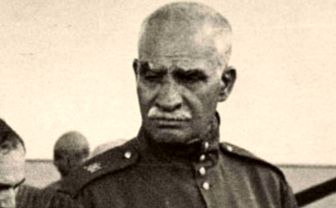

In 1935 CE, when the news spread about the new law on dress code [including the removal of hijab] and the possibility of its application increased, some of the middle-ranked scholars of the seminary – on the top of whom, Imam Khomeyni – requested Ayatollah Haeri to send a telegraph to Reza Khan, to leave a record for history and possibly, stop this great crime. A telegraph was sent to Reza Khan which received Prime Minister Mohammad-Ali Foroughi’s deceitful reply. Being a witness to the incident, the Imam relates the story as follows:

“[Do you know] how was the state of our late Shaykh (May God be pleased with him) [during the time of Reza Khan]? In one incident (perhaps, the incident of hijab removal) the late Shaykh (Shaykh Abdolkarim) sent a paper (a telegraph) to Reza Khan and warned him about this law. He [Reza Khan] did not reply. Prime Minister Foroughi said: ‘It was presented to his majesty and he said you’d better mind your own business.’”

The banning of the hijab was a shocking incident for both Iranian people and religious leaders and scholars in Iran and Iraq. It was regarded as a national disaster. After the exile of Ayatollah Qommi to Najaf, Shi’ah scholars residing in holy cities in Iraq, who were far from the Reza Khan’s reign and naturally enjoyed more political freedom, were informed about the anti-Islamic measures of Reza Khan more than before. Thereafter, they issued several fatwas on the forbiddance of the Pahlavi cap and the banning of the hijab, which did not get practical publicity due to the fear and horror because of the regime’s heavy crackdown in Goharshad Mosque. After Reza Khan departed from the country and in the relatively free political atmosphere afterward, scholars and religious leaders in Iran too issued fatwas against the banning of the hijab of women.

During the second half of Reza Khan’s reign, in which pressure and security persecution had exceeded its limits, the Imam held sessions on “Ethics” in the school of Feyzieh; perhaps hoping that in addition to teaching moral virtues and fighting against moral vices – including cowardice – he could pave the spiritual and educational grounds for fighting against the regime, or at least save the people, especially the youth, from falling into different traps which Reza Khan’s regime had set up for them.

In any case, even this little circle did not remain unnoticed by Reza Khan’s agents and they wanted the Imam to close his class; nevertheless, the Imam refused to cancel his class by himself and told them, should they deem this class inexpedient, they must themselves dissolve it. Perhaps by this suggestion, the Imam meant to show the level of the regime’s dictatorial nature to his students.

The Imam’s theoretical stances can be traced through his lectures and writings. These stances have two sides; on the one hand, he criticizes the narrow mindedness, immobility and political passivity in the Islamic seminaries, and on the other hand, he criticizes Reza Khan’s rule and the continuity of his system after his departure.

Several political failures that had been brought for the clergy by foreign operatives after the constitutionalism, along with the intense anti-Islamic and anti-clerical propaganda under the banner of nationalism, added to the passivity of the clergy more than before. Such propaganda, which was carried out to push away the clergy from political involvements, got momentum after the consolidation of Reza Khan’s reign, and for the years to come it was intensified and more obvious by creating numerous obstacles, heavy crackdowns, arrest, imprisonment, and exiling many of the well-known scholars. Such propaganda and measures, not only entailed political and social isolation of the clergy but also left several psychological and mental negative effects in the Islamic Seminaries. One of such negative effects was the acknowledgment of “the separation between religion and politics” and indifference to political affairs.

“Another plan that they had made previously along with this [destruction of the clergy] and they developed it, was that they promoted the idea: “what does a clergyman have to do with politics” so much that scholars too – most of them – had believed [it] and if anything about politics were told, they would say “this is politics and not our business.” If a scholar intervened in a situation related to society, to some of the people’s problems – for instance, he wanted to confront a government – the rest of the scholars were convinced that they must not intervene in politics and would exclude him from themselves as a “political clergyman.” [According to their belief] a clergyman’s duty was to go from his home to the mosque and in the mosque, if he wants to preach, he must preach about religious laws and ethics. He should not say a word about the problems in society. That is, they have been grown up like this and the propaganda had affected their mind to this level.”

Such political self-censorship in the prevalent culture of the seminaries at that time was parallel and complementary to the regime’s propaganda, so that “if anyone talked about ‘Islamic government’ it was as if he has committed the greatest sin, and the phrase ‘political clergy’ had become equivalent with irreligious clergymen.” Even when it was reputed that one of Qom’s clergymen had newspapers in his house, he was blamed and rebuked by his peers.

In such a situation, political ignorance among the clergy was considered not a flaw or shame, but a ‘virtue.’ Such taste or perspective, which had become a disposition for many of the clergymen at that time, left another negative effect and that was the restriction of the scope of Islamic teachings, including jurisprudence, which was the result of political passivity and indifference.

“When the slogan of separation between religion and politics was implanted and, in the mindset of the ignorant, jurisprudence was seen as submerging oneself in individual worshiping regulations and, automatically a jurist was not allowed to pass over this border to interfere in politics or the government, a clergyman’s stupidity in his interactions with people turned to be a virtue. In some people’s opinion, the clergy was only respectable or venerable when he was filled with stupidity from head to toe; otherwise, a political clergyman or a clever and informed scholar was seen as deceitful. And this was among the prevalent issues in the seminaries that anyone who walked more lopsidedly was [regarded as] more religious.”

The Imam could not accept that narrow sight and superficial jurisprudential thinking, so he criticized and blamed its advocates in a serious and hard way. “He hated those clergymen who rejected Islamic philosophy and wisdom and would regard the teaching of philosophy and mysticism as forbidden or disliked. He called them superficial, fanatic and ignorant. For many times, he had been the subject of their objection and rejection, however since he was very well-versed in Jurisprudence and its principles and had sessions of discussions with jurists and usulis, no one would dare to attack him directly or forbid his classes on philosophy or mysticism.” In his book “Forty Hadith,” he writes in a sarcastic tone “those who try not to miss the preferred rituals and etiquettes of sleep, food and the washroom, have ignored the divine teachings which are the ultimate aim of the awliya (friends of God).” Also, he severely criticizes those sanctimonious, who have turned away from the inner truth of divine obligations – at the top of which, prayer, which is the means of ascending and nearness to God for the faithful, and the pillar of the religion, and have ignored all its spiritual aspects and divine mysteries – and have restricted the truth of prayer to the accuracy of word pronunciation, rather they regarded the pronunciation as an indication of sanctity and spiritual purity. Such criticisms in addition to holding classes on philosophy and mysticism by the Imam – which was abnormal in seminary curriculum – were enough reason to make him and other “true religious scholars who had been educated in the very seminaries and changed their way” the subject of severest accusations and attacks – even accusing of polytheism – by the very fanatic and superficially religious people.

“Learning foreign languages was considered blasphemous, and philosophy and mysticism were regarded as heresy and polytheism. Once my little son, Mustafa, drank from a bowl of water in the school of Feyzieh, they washed and drained the bowl, for I [his father] used to teach philosophy.”

By the “painful reality which he had seen or heard” the Imam meant the narrow and close mentality that had existed in the Islamic Seminaries, from the past to that time – and also continued after it. According to the Imam, narrow-minded deemed “the denial of mystics’ spiritual status” and hostility to them as their religious obligation. But [in reality] “those who deny the spiritual status of mystics do this because their selfishness does not allow them to accept their ignorance, so they automatically deny what they don’t understand for their selfishness to remain untouched.” Perhaps, the Imam’s stressed advice at the end of his mystical book “Misbah al-Hidayah” in which he says “You must never disclose these mysteries to the unqualified, or be generous in spreading them where it is not suitable;” is about those very narrow-minded and selfish unqualified people, who due to their deprivation of understanding those high teachings, would rise in opposition to their advocates; in addition to the fact that usually profound mystical teachings should be learned in a proper context and under-qualified and well-known teachers.

Another dimension of the Imam’s criticism is directed toward anti-national and anti-Islamic programs of Reza Khan, which were followed under the cover of nationalism and modernization. A note that shouldn’t remain unsaid is that the Imam’s criticism of narrow mindedness and political passivity in seminaries was the result of his direct observation of what was going on in seminaries as he had lived and been educated there; however, his source or sources of information about the nationalist and modernist measures of Reza Khan is not clearly known.

The Imam’s criticisms of Reza Khan’s modernist measures show that he had accurate information and straight facts about those incidents. Because those incidents took place out of the Seminary and in the circles of politicians and intellectuals in big cities, naturally his sources of information must have been either the regime’s official press or some trustworthy individuals who had official positions. Doubtless is the fact that the Imam’s repeated references to the newspapers of that time show that one of his main sources of information was the regime’s official press. In the second half of Reza Khan’s reign when intensified anti-Islam and nationalist propaganda was pumped into society through the press, the Imam was aware of this general approach.

“At the time of this unworthy individual [Reza Khan] who had corrupted our country, the Revered Prophet (s) was insulted in newspapers; … these politicians set up a session in which they criticized the triumph of Islam over disbelief [=Sassanid dynasty] and these [so called] intellectuals took out a handkerchief and cried for Islam had defeated the King of Iran [Yazdegerd III] – the Shah of the time. Their poets composed poems, their writers wrote and their orators said.”

But, was all this propaganda and politicians’ show of affection to the country and patriotism, truly the result of their honest national zeal?

“Such hypocritical and populist words that these politicians had taken as their habitual comments, and claimed sincerity in their patriotism, was to deceive the masses and at the same time, to take their own benefits; otherwise you can test any of them to see the reality of their claim yourself.”

“All know that unless there are several million tomans expected from a seat in the parliament, hundreds of thousands of tomans will not be spent to take one, and a single vote will not be bought for one or two hundred tomans. Those who have taken the heavy burden of ministry, ‘just for the sake of the country and only to serve the dear nation; go and compare before and after their position as minister, see their ownership documents, so that you may realize this better.”

leave your comments