In the Name of God, the Most Compassionate, the Most Merciful

Author’s Note

“The Stories of the Revolution” is a total of about twenty in number, and children play the main role in all of them. These stories were sent to me or entrusted to me by children from different parts of Iran at the height of our sacred revolution. They were either given to me through my acquaintances or were handed to me during my journeys all around Iran. In the climax of the revolution, these stories couldn’t be typeset. I arranged six of them and converted them from the simple report form to story form; I wrote them out with a pen and published them. These kinds of stories were called “white cover” back in those days because no one had the time to design and publish a nice cover. After publishing these six volumes, the serious post-revolution works began; I went to the Red Crescent Organization and worked day and night to start the “Red Crescent Volunteers Organization.” Afterwards, the entanglements and pressures of life didn’t leave me time to turn those glorious, bittersweet adventures into “stories.” I gradually arranged six more stories, but didn’t finish and publish them. The rest of the adventures and outlines were left unfinished.

This year – 1994 – the first five stories are being reprinted with the effort of “Hozeh Honari” in a beautiful format, along with illustrations. You are looking at it now. With hope in God, if I stay alive, I will publish the other six stories next year, on the anniversary of our great and glorious revolution. And if I remain alive for more, I might publish the other eight in the upcoming years…

These stories, which are about the nooks and corners of the biggest revolution in human history, are a dear memento; I want them to be left behind from me and the children who entrusted these notes and memories to me.

I had a faithful co-worker who helped me in the compilation of some of these stories and I would like to thank him. So, thank you, Mr. Shakour Lotfi.

And also, it wouldn’t be right to not thank the first publisher of this series; because back in those wonderful days, these kinds of works needed a lot of courage. So, with thanks to Farzin Publications.

Our revolution was such that even if hundreds of big books were written about it, it would still not suffice. These few small books are a dim star in the clear and unlit sky.

Thank you and goodbye

Nader Ebrahimi

November 6th, 1993

--

Our house was right behind the Air Force base; I mean, it still is. That night, we were watching the television program on Agha’s return. A few days ago, on the morning that Agha was coming back from his journey, my parents and I and all of our neighbours had gone to see him. All of our next-door neighbours, our entire neighbourhood, and all the people were there. Oh my God! How many people! How many people! We weren’t able to see Agha. It was very crowded. Our spot wasn’t good either. My father lost his hat, and my mother lost her chador. I suddenly saw my mother who had nothing on her head and was crying. She wasn’t crying for her chador; she was crying because of Agha. She wished to see our Agha; she really wished to see him; but well, a lot of people weren’t able to see Agha.

That was why we had gathered around the television that night. I took a glance at Agha and took a glance at my mother. She was absorbed in watching Agha. She kept praying for him nonstop. She murmured some things under her breath and blew them to the television. One of Agha’s bodyguards was sitting on the car’s roof; whenever his leg came in front of Agha’s face, my mother would fret, “Get your leg out of the way! Don’t you see we’re watching?”

My father would quietly say, “He can’t hear your voice, lady! It’s a film. It’s from a few days ago.” But my mother didn’t pay any attention to these words. As soon as she saw Agha’s face through the car window, she would say, “Oh God! Protect him. Keep him away from dangers.”

Anyway, we were absorbed in the television when the sound of the tanks raised… We were of course used to these kinds of sounds. We were used to the sound of bullets, grenades, tear gas and these sorts of things. But after a few minutes, we suddenly heard a very strange sound.

Father said, “It’s the sound of a shell.”

My uncle said, “God have mercy on us.”

Then we heard the rapping of machine guns and everything turned into chaos.

My uncle ran to the rooftop. I ran after him. My mother shouted, “Crouch down and walk!”

We got to the rooftop and saw the battle. The neighbours were out on the rooftops just as quickly. Everyone said, “They have attacked the Air Force. The soldiers of the fleeing Shah have attacked Agha’s soldiers…”

One of the Air Force soldiers got himself behind the wall in a flash and yelled, “Help! Help! The Royal Guard has attacked the Air Force! They’ll kill all of us.” He turned back and ran toward the buildings. I was so glad that he didn’t run away to save his own life. He went to fight alongside his friends.

All of a sudden, the sound of “Allahu Akbar!” (God is the Greatest) raised from everywhere. One house, ten houses, a thousand houses, and all the city’s houses… The Air Force base trembled. The whole world trembled. How the people shouted! Oh, God! I shouted with all my voice, “Allahu Akbar! Allahu Akbar!”

My body was trembling. I was shaking on the inside.

My mother had come too. Everyone had come. There was fire and the sound of gunshots and shouts. But the sound of “Allahu Akbar” and “La ilaha illa Allah” (There is no god but God) was louder than all the other sounds. It was a sound that seemed to come from the sky, from above the clouds…

Two people came running from the alleys on the other side of the Air Force base and drew near. They were yelling, “They need help! They need help! They’re killing all of them.” They threw a letter from the other side of the wall. “The Imperial Immortal Guard of the traitor Shah has attacked the Air force. It has attacked with tanks. Call the rangers. Whoever has a weapon must help! They’re killing the nation’s airmen! Come on! Hurry!”

Two men were shouting and going…

Father said, “How can we help them?”

My uncle said, “You just keep shouting and informing the people. I’ll go find some fighters.”

My uncle left. I ran into the staircase and shouted, “Should I come too?”

My uncle answered from the bottom of the stairs, “Come.”

I swiftly got myself on his side. We ran in the streets and shouted, “Allahu Akbar! Allahu Akbar! Help! Help! They’re killing the airmen…”

But it wasn’t only the two of us running now. Many people were running. It had gotten very crowded.

The sound of machine guns, the sound of shells, the sound of “Allahu Akbar,” the sound of small children crying, and a thousand other sounds…

I saw a group who were running toward Tehran-e No Street with sticks and knives. Could you stand in front of tanks and machine guns with sticks and knives? I don’t know, but they were going to fight anyway.

We got in front of a house and my uncle stopped. I was out of breath. The door was open. My uncle yelled, “Jafar! Jafar Agha!”

A very small girl came out and said, “My uncle left with his gun.”

We went in front of two other houses, but there was no one home. Everyone had gone to fight. The people in our neighbourhood liked the “Air Forces” very much. They didn’t use to like them as much before; but since they recognized that they are with the people and they support the revolution, they adored them. My mother took pride in kissing the uniform of three Air Force officers. My mother would say, “I’m responsible for my own sins; once, I even wanted to kiss the hand of one of them…”

Then, my uncle ran to the corner of Tehran-e No Street. Oh, God! It was so crowded.

Everyone was doing something, but I couldn’t figure out what they were doing. We thought we had taken action very quickly, but then realized that we had even been late. My uncle found Jafar Agha in that rush. Jafar Agha was laying down behind three full sandbags.

My uncle said, “Jafar! What should we do?”

Jafar Agha said, “I phone called the guys to come. For now, make as many trenches as you can!”

I said, “Nothing is going on here. The war is inside the Air Force base. They’re killing everyone over there.”

Jafar Agha didn’t answer, but my uncle repeated my sentence and Jafar Agha had to reply.

“When we get together, we’ll split into two groups. One group will attack, and one group will stay behind the trenches.”

I asked my uncle, “What are we supposed to do now?”

Jafar Agha said, “Find empty sacks! Fill them with soil and bring them here!

My uncle said, “Do as he says!”

I ran into our own alley and cried, “Empty sacks! Empty sacks! They want to make trenches.”

A few of our alley’s children arrived. We gathered seventeen sacks, as quick as lightning.

My mother came and said, “Come inside the yard and take soil!”

We ran inside the yard. My mother started to dig with a shovel. Sometimes she would spit on her palms and switch hands. She had become like men. She had wrapped her chador around her waist. Her hair was in her face. She was sweating and shovelling. If I said, “Mother, cover your hair”, she would probably say, “I’m responsible for the sin. Do your own job.”

Reza, our neighbour’s son, went and brought a needle and string-like lightning. We quickly sewed up each sack that was filled; four of us held the four corners of the sack and ran to the corner of the street. Our strength had doubled.

The noises, screams and shouts would make you deaf. Everywhere was filled with smoke and a load of tires were burning in the middle of the road.

The fifth time we went, there wasn’t room for us to pass anymore. Reza would shout, “Sacks for trenches! Open the way!”

The sixth time we went, Jafar Agha wasn’t behind the trenches anymore; instead, my uncle was there with a gun! He was sitting, holding a gun, and watching the end of the street. There was debris on his face. The smell of burnt tires would choke you.

I asked, “Where did you get the gun from?”

My uncle said, “Someone had two.”

Uncle looked awesome. I still remember the days when he came home wearing his military service uniform. He knew how to shoot and had worked with a machine gun too.

Uncle said, “We don’t need any more sandbags here. Go to the other streets.”

We ran and took the filled sandbags to the other streets. While passing by the Air Force base’s wall, we suddenly saw a sergeant. He pulled himself up and sat on the wall. How he felt! I can’t even describe it. Tears flowed down his face as he said, “We’ll kill them. We’ll kill all of them. They opened fire on my brothers…”

My brothers. Then he said, “Hurry.” He bent down to the other side and got a machine gun. I was beneath the wall. He said, “Catch, boy!” and I caught it and put it down. Then, Reza did the same. People gathered. The sergeant who was on top of the wall said with tears, “No one touch! They’re all full. Those who know how to shoot, step up. Those who have gone to military service, step up.”

Reza and I stood beside the guns, machine guns, and ammunition boxes to make sure no one touches them. The sergeant came down the wall. After him, another person jumped down, and then another person. The second person had been shot, and his pants were full of blood from his knee downward. But how he looked! It was as if he hadn’t been shot at all. They helped him get down. Then, they wanted to take him to the house on the opposite side and wrap his wound. He said, “Bring the first aid supplies behind the trenches!” and he took a machine gun and ran behind the trenches, crippling.

The sound of the tanks and trucks raised again. The sound of Allahu Akbar and La ilaha illa Allah, the sound of shells and guns, and grenades and a thousand other sounds. Oh, God! What a night it was! Even the old grandparents went running.

Reza and I went to the corner of the street. We saw three tanks and a number of trucks coming from Fouzieh Square, but they approached with great difficulty. There were many different things placed in the middle of the street. There was fire everywhere. The tanks fired and came closer. Something whistled above my head and the wall behind me collapsed. Dust went up into the air. The wounded sergeant yelled, “Lay down!”; then he kneeled, pointed his machine gun at the tank and shot. Fire came out of his machine gun’s barrel. His entire body trembled as he kept shooting. In the midst of smoke and fire, I saw three people who ran to the middle of the street and approached the first tank; but all three of them fell down, rolled on the ground, and didn’t get up again.

The wounded sergeant came back and shouted at me, “Bring ammunition, boy!”

Reza and I ran to the end of the street and told one of the sergeants, “They need ammunition behind that trench.” The airman handed a box to Reza and said, “Run!”

Reza left and I lost him. Three people were taking cotton swabs, bandages, and these sorts of things. I didn’t go after them. I had to be in a place where I was useful. I ran among the people to the street where my uncle’s trench was. Now, ten people were sitting behind the trench. However, only three of them had guns. I got myself to my uncle and said, “Do you need anything?”

My uncle didn’t look at me. He was concentrating on something else. A young man who was holding a big bottle said, “Matches!” I ran back and shouted, “Matches!” Then I went into the crowd and shouted again, “Matches!”

Someone handed me a box of matches. I ran back and gave it to the young man. He stood up, lit the bottle, and ran toward one of the trucks. He was so brave for doing something like that. I thought to myself, “He will fall right now and not get up anymore, like the other three people who attacked the front tank.” But the young man threw the bottle; and I saw his arm, the same arm he had thrown the bottle with, catch on fire up to his shoulder.

The bottle hit the truck and flames went up from the whole truck. A few people shouted, “Long live the brave ranger!” The young man whose arm was like a torch came back toward the trench.

Someone yelled, “Blanket!”

I ran to the first house and shouted, “Blanket!”

Someone handed me a blanket. I went back to the young man whose arm was burning. I didn’t know what to do. Someone took the blanket from me and wrapped it around the young man’s arm. The young man was twitching with pain and moaning. I looked at the truck; it was burning, but they were still shooting from inside it. Four airmen arrived with their machine guns.

I said, “That truck…”

One of them handed his machine gun to his friend, pulled a grenade out of his bag, jumped on top of the trench, and ran toward the truck. He ran in the same direction that was blazing with fire. When he got very close, he threw the grenade.

Oh my God! The truck suddenly exploded and its pieces went up into the air. Some things hit us in the face.

A group shouted, “Allahu Akbar! Allahu Akbar!”

There was the smell of blood, burnt flesh, and the smell of many other things, and everywhere was full of people. If they threw a grenade in the street where I was, two hundred people would get killed.

I don’t know where all those people, all those guns, all those bullets, all those sandbags, all those gasoline-filled bottles, and all those shooters had come from so quickly. It was as if everything came boiling out of the ground, or pouring from the sky. It reminded me of the story of the magic pumpkin and the person who beat it with a stick and said, “Soldiers!” and an army came out of the pumpkin. The neighbourhood was filled with strangers, unknown fighters, and people who helped the fighters. One would bring boxes of ammunition, one would bring cotton swabs, medicine, and bandage; another would bring a whole lot of white cloth; another one would bring blankets, and a few people would come with stretchers (or things that are like beds without legs) and carry the injured ones away.

Now the entire street was divided into two parts: one part was called the “warfront” and the other part was called “behind the warfront.” The warriors were in the warfront and the other people were behind the warfront, or they would keep going and coming between the warfront and behind the warfront.

The injured ones were rushed behind the warfront. There, the ladies worked very quickly. They washed the wounds with warm water and bandaged them. I saw Mehri, Reza’s sister, who was working behind the warfront. I saw my mother a few times too, behind the warfront of this and that street. Sometimes she passed by me and didn’t look at me. And one time, I saw my father too, who was carrying a wounded airman on his shoulder and was taking him behind the warfront. I went after him to help. My father put the airman down and stood.

The men and women gathered around the airman and looked at him; they put their heads on his chest and listened. A few people said, “Ashhadu an la ilaha illa Allah…” (I witness that there is no god but God).

My father burst into tears and left.

The traitor Shah’s guards’ soldiers kept shooting from their cars and tanks.

Instead, the airmen, the good men of the Air Force, were always beside the people. I saw an airman behind every trench I went to. In that hustle and bustle, some of them were teaching the youths how to shoot. It was an all-out war; a big and real war; a war I hadn’t seen in any movie.

The sound of ambulance sirens could be heard from a distance.

Many people were crying, but I couldn’t cry.

I went to the warfront to see if anyone needed anything. An airman yelled at me, “If you want to do something, go behind the warfront. It’s dangerous here.” And I wasn’t offended that he had yelled at me. I went behind the warfront and someone said, “We’re out of cotton swabs.”

I said, “I’ll go get some for you right away.”

I ran one street down and said, “They need cotton swabs there.” They handed me two packs and I went back, and I saw them putting a wounded airman down. I saw his face. It was he. It was him; the one who had yelled at me a minute ago. Blood was gushing from his forehead. His eyes didn’t shine. I bent my head in that turmoil and kissed his blood-stained face and burst into tears.

A lady asked, “Is he your brother?”

I didn’t say anything and only cried. Well, he was my brother, wasn’t he? All of them were my brothers. Plus, this one was even closer than a brother to me. He was the one who hadn’t let me get killed.

I heard the lady say to a few other people, “I think he’s the brother of the boy who’s crying. Poor thing. He bent down and kissed his brother’s face.”

They gathered around me and embraced me and said, “You should be proud that your brother got killed because of his people. Congratulations on his martyrdom.”

I ran crying and went to the trench where my uncle was. I thought, “What in the world would I do if he has been shot too?”

I got behind the trench and saw my uncle. They had wrapped a blanket around his body.

I said, “Are you ok, uncle?”

He turned, and when he turned I saw that his eyes didn’t shine and his body was bare. His left hand was bandaged. I didn’t have to ask anything anymore.

Two tanks were retreating. The sound of hundreds of shots could be heard; the sound of a hundred kinds of explosions.

A group of ten or twelve airmen and other youths who were hiding in ambush jumped into the street and closed the way on the retreating tank. What courage and bravery! What chaos! What a noise! What a killing!

I saw the tank stop. A soldier who had put his hands on his head came out of the tank. The youth pulled the soldier down and then, everyone quickly retreated; and the tank, that huge tank, suddenly exploded.

The people shouted again.

The warriors destroyed one tank. This was the warriors’ biggest victory.

Then, another tank came toward my uncle’s trench. The rapping of machine guns could be heard non-stop, and the tank approached with speed; it came straight at the trench, carelessly. Dear God! The warriors got up and ran like wind. My uncle couldn’t get up. I held his arms and pulled him up. He stood and then ran. I ran after him too. The tank came inside the trench and its barrel went straight into the wall and stopped.

Everyone shouted, “Allahu Akbar! Allahu Akbar!”

I heard someone say, “There’s the second one!”

Then the warriors returned to their trench. You couldn’t find a trench better than this. They pulled the sandbags around the tank and got ready for war again.

All of a sudden, a group started shouting “Helicopter! Helicopter!”

I looked up at the sky and saw two helicopters coming over the Air Force base. Their lights were on and were flying very low. I saw fire coming out of the machine gun barrels that were on the rooftops, but I didn’t see the helicopters catch on fire and fall.

The helicopters turned back and left.

I ran behind the warfront for the hundredth time. I saw that everyone was busy doing their job and no one needed me. So I ran to the other streets and then the other streets; wherever there was something to do, I would do it. Someone wanted water, someone asked for fabric, someone needed ammunition, someone needed gasoline; and most of all, they needed blankets to cover the wounded who were resting in some of the houses.

The injured ones who were feeling better and were sitting beside the street, behind the warfront, asked, “How’s everything?”

I replied, “Great! We destroyed two tanks. We put a truck on fire. We made the enemy’s helicopters flee.”

Just as I was looking around, I suddenly saw an opening in one corner of the Air Force base’s wall. I guess a tank shell had broken the wall. I went in through the opening and went closer till I reached the back of the first building. The bullets went whistling past all my sides, but I don’t know how I felt that I wasn’t afraid of anything; I didn’t even think that one of those bullets might hit me. A sergeant who was running from this side of the building to the other saw me and shouted, “Get away from here!”

I dared to yell, “Do you need anything? I’m from behind the warfront.”

The sergeant yelled, “We have a thousand wounded.”

I replied, “I’ll get help right away.” And I returned to the opening in the wall and ran swiftly. And as I was running, my left shoulder started to burn and I fell to the ground. I got up again, ran, fell again, and got up. I reached behind one of the warfronts and shouted, “They need help inside the Air Force base. They have a thousand wounded people there.”

Someone asked, “How can we get inside?”

I said, “Right back there, the wall is broken. I’ll show you!”

Twenty people ran toward the opening all at once. I didn’t go anymore. My knees were trembling. I had a bad headache. My eyes went black. And worst of all, my left shoulder burned. I sat down and stretched my legs out; I looked at my pants which were full of bloodstains. At first, I thought that its water. I rubbed my hand over it and held it in front of my eyes. My fingers were coloured. Then I saw my shirt was full of blood. I thought, maybe I’ve been shot, but I couldn’t think anymore. I guess I fainted…

***

I heard my mother’s voice who was saying, “That’s my son. Where has he been shot in?

Someone replied, “In his left shoulder.”

My mother asked, “Is he alive?”

Someone else answered, “Yes, Mother. It’s nothing serious.”

My mother said, “Put him down. God bless you.”

I opened my eyes and looked at my mother! It was as if she didn’t know me. I was a wounded person just like the rest of the wounded people. She said, “It’s nothing important, son!”

I said, “I know.”

***

At 4:30 in the morning, after six hours of fighting, we defeated the enemy. The noise had almost dropped. Single gunshots and ambulance sirens could be heard. But the sound of tanks and shells had stopped.

My uncle said, “You have to get going sooner! We have to get food to all the trenches and get everything back in order.”

I said, “Will do. Is Jafar Agha… alive?”

My uncle said, crying, “He was martyred.”

I said, “Do you still have your gun?”

He said, “Yes, I won’t put it down, Mahmoud. I won’t put it down as long as the enemy exists.”

Now that I look back, I think everything seemed like a dream; a strange and unbelievable dream. Many of the airmen were killed, many… They fought really well.

I tell my mother, “A lot of the airmen were killed; right, Mother?”

My mother says, “Instead, their children can proudly walk in this country; proudly and with honour!”

My father sadly says, “What are you talking about, lady? Most of the ones who were killed were so young, they weren’t even married let alone have children.”

My mother says, “All history books will write that the Air Force had a very big role in the victory of the revolution. They can at least write this, can’t they?”

My father softly replies, “Yes…they will definitely write this; definitely. This nation will remember the sacrifices of the Air Force until the end of time…

I whisper, “There was Jafar Agha too; my uncle’s friend.”

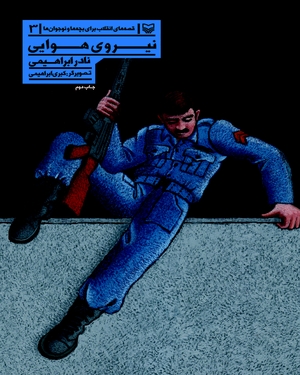

Stories of the Revolution for Children and Youths – 3

One of the Air Force soldiers got himself behind the wall in a flash and yelled, “Help! Help! The Royal Guard has attacked the Air Force! They’ll kill all of us.” He turned back and ran toward the buildings. I was so glad that he didn’t run away to save his own life. He went to fight alongside his friends.

Sureye Mehr Publication

Office of Literature on the Islamic Revolution

Archive of Culture and Art

leave your comments