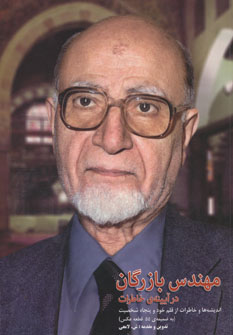

Mahdi Bazargan was an Iranian scholar, academic, long-time pro-democracy activist, and head of Iran’s interim government, making him Iran’s first prime minister after the Iranian Revolution of 1979. He was the head of the first engineering department of the University of Tehran. A well-respected religious intellectual, known for his honesty and expertise in the Islamic and secular sciences, he is credited with being one of the founders of the contemporary intellectual movement in Iran.

Bazargan was born into an Azerbaijani family in Tehran on 1 September 1907. His father, Hajj Abbasqoli Tabrizi (died 1954), was a self-made merchant and a religious activist in the bazaar guilds. He completed his elementary and high school education at Tehran’s Servat, Soltan, and Dar al-Moallemin Schools, and participated in a European scholarship competition in 1929, and was sent to France by the Ministry of Public Benefits in the same year.

When in France, Bazargan attended Lycée Georges Clemenceau in Nantes and was a classmate of Abdollah Riazi. He then studied thermodynamics and engineering at the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures (École Centrale Paris).

After his graduation, Bazargan became the head of the first engineering department at the University of Tehran in the late 1940s. He was a deputy minister under Premier Mohammad Mosaddeq in the 1950s. Bazargan served as the first Iranian head of the National Iranian Oil Company under the administration of Prime Minister Mosaddeq.

Bazargan co-founded the Liberation Movement of Iran in 1961, a party similar in its program to Mosaddeq’s National Front. Although he accepted the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, as the legitimate head of state, he was jailed several times on political grounds. As a consequence of criticizing the Shah’s White Revolution, LMI members were arrested and imprisoned.

Bazargan himself was sentenced to ten years imprisonment but released on a royal pardon, after four years and nine months. Following his release and throughout the 1970s, Bazargan kept a low profile but was actively involved in some intellectual debates — in a dialogue with the clerics on the meaning of government; in a critique of Marxism; and in elaborating a modern interpretation of Islam.

During the Pahlavi era, Bazargan’s house in Tehran was bombed on 8 April 1978. The underground committee for revenge, a state-financed organization, proclaimed the responsibility of the bombing.

When political controls relaxed in 1977, Bazargan re-entered the open political arena through the Iranian Committee for the Defense of Freedom and Human Rights, the first independent human rights organization in Iran’s history, in which he was elected as chairman. An established record of activism in Islamic and national circles promoted Bazargan to the forefront of Iranian opposition circles, and it was on this basis that the emerging leader of the revolutionary movement, Ayatollah Khomeini, appointed him as the first post-revolutionary prime minister.

As popular uprisings against the Shah raged, Bazargan’s political activities became even more vivid. In September 1979, after Ayatollah Khomeini arrived in Paris, he also travelled to France to meet with the leader-in-exile. At the meeting, Bazargan was tasked with preparing a list of the members eligible for membership in the Revolutionary Council and providing it to the leader of the revolution.

On 4 February 1979, Bazargan was appointed prime minister of Iran by Ayatollah Khomeini, and in the hope of reforming the state bureaucracy, formed his cabinet. His nine-month government was, however, to preside over the greatest defeat suffered by the liberal moderates at the hands of the radical and revolutionary movement. He was seen as one of the democratic and liberal figureheads of the revolution who came into conflict with the more radical religious figures as the revolution progressed.

Despite Ayatollah Khomeini’s recommendations, Bazargan government ministers were mostly chosen from members of the Liberation Movement. As prime minister, Bazargan sought to solve problems routinely, less in revolutionary ways, and always spoke of step-by-step politics in government programs.

Although pious, Bazargan initially disputed the name Islamic Republic, wanting the Islamic Democratic Republic. He had also been a supporter of the original (non-theocratic) revolutionary draft constitution and opposed the Assembly of Experts for Constitution and the constitution they wrote that eventually adopted as Iran’s constitution. Seeing his government’s lack of power, in March 1979, he submitted his resignation to Ayatollah Khomeini. Ayatollah Khomeini did not accept his resignation, and in April 1979, he and his cabinet members escaped an assassination attempt.

Bazargan resigned, along with his cabinet, on 4 November 1979, following the American Embassy takeover and hostage-taking. His resignation was considered a protest against the hostage-taking and a recognition of his government’s inability to free the hostages, but it was also clear that his hopes for liberal democracy and accommodation with the West would not prevail.

Bazargan continued in Iranian politics as a member of the first Parliament of the newly formed Islamic Republic. He openly opposed Iran’s Cultural Revolution and continued to advocate civil rule and democracy. In November 1982, he expressed his frustration with the direction the Islamic Revolution had taken in an open letter to the then speaker of the parliament Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani.

His term as a member of the parliament lasted until 1984. During his time, he served as a lawmaker of the Liberation Movement of Iran, which he had founded in 1961, and abolished in 1990. In 1985, the Guardian Council denied Bazargan’s petition to run for president.

Throughout the 1980s, Bazargan’s insistence on liberal politics, scorned by four groups. First were the modernist/monarchists, who in their apolitical model of social development, had no time for Bazargan’s indigenous concoction of open, active, religious, and liberal politics. The second group represented the traditional religious community led by the senior clergy, who jealously guarded the mystical world of their creed and saw Bazargan’s notion of democratic rule as a threat to their elitist concept of the right of the clergy to interpret the religious text.

The third group which stood against Bazargan was that of the Marxists, including the Islamic/Stalinist Mojahedin-e Khalq Organization. This group saw Bazargan as a “petty-bourgeois bazaari merchant” whose notion of liberalism was rooted in his greed for personal profit. The last, but most influential, group was that of the radical Islamists, the main benefactors of the 1979 Islamic revolution. They saw Bazargan as the personification of western corruption amongst the ranks of the believers and thus sought to isolate him.

The 1990s could be termed as a period of strategic ideological success for Bazargan and his liberal colleagues. On the one hand, the collapse of the Soviet Union and on the other the futility of 15 years of anti-government terrorism and state terrorism, had initiated a far-reaching revisionist trend among all political activists. The word liberal was a derogatory term popularly understood to connote a weak, wishy-washy, and petty opportunistic mentality in politics. Almost all Iranian political groups sought to present a liberal image of tolerance and moderation.

Bazargan is a respected figure within the ranks of modern Muslim thinkers, known as a representative of liberal-democratic Islamic thought and a thinker who emphasized the necessity of constitutional and democratic policies. In the immediate aftermath of the revolution, Bazargan led a faction that opposed the Revolutionary Council dominated by the Islamic Republican Party and personalities such as Ayatollah Beheshti. He opposed the continuation of the Iran-Iraq War and the involvement of clerics in all aspects of politics, economy, and society.

Consequently, he faced harassment from militants and young revolutionaries within Iran. Bazargan believed that there is a link and relation between politics and religion, but did not believe in Political Islam.

In the more than 50 books and pamphlets that left behind, Bazargan is known for some of the earliest work in human thermodynamics, as found in his 1956 book Love and Worship: the Thermodynamics of Human Beings, being written while in prison, in which he attempted to show that religion and worship are a byproduct of evolution. His other works include The Way Passed, The Evolutionary Course of the Quran, and The Iranian Revolution in Two Phases.

Bazargan married Malak Tabatabai in 1939. They had five children, two sons, and three daughters. He died of a heart attack on 20 January 1995 in Switzerland and was buried in a family tomb in Qom.

Archive of The History of the Islamic Revolution

leave your comments