The issue of fashion and clothing trends is a core subject within the Iranian cultural discourses. The diversity of clothing and the decisions made about it reflect in political disputes, educational regulations and the rules of normative behaviour. The dominant discourses, with structural clothing patterns such as national and formal dress, try to homogenize the dress code whereas other discourses promote the diversity of clothing trends by emphasizing the individuals’ freedom of choice.

People’s clothing either indicates that they follow the norms derived from the dominant discourse of power or show resistance to these norms. The issue of the hijab in Iran is the source of disagreement between the two rival discourses; on the one hand, there is the religious discourse in which the concept of chastity gives meaning to clothing, and values such as the sanctity of the family would form the order of discourse when considered with other concepts including chastity, immunity and hijab.

While emphasizing the purification of the soul, the religion disregards physical fitness and characteristics by promoting loose and long clothing. On the other hand, in the rival discourse (non-religious discourse), the originality of the self and personal freedom gives meaning to the issue of clothing and covering, and the body as the “objective self” is manifested in the clothing which in turn are used for showing off the body. In this discourse, colourful and transparent clothing indicates physical fitness and abilities. In political discourse, clothing has a “unifying” and homogenizing function.

Therefore, by defining and determining the “appropriate clothing trends,” the political systems seek, on the one hand, to exercise control over the body and individual choices, and indoctrinate a unique identity based on specific national, patriotic, historical, or myth definitions of superior or appropriate clothing on the other.

Social Modifications of the Dress Code

When Reza Shah, at his coronation ceremony, did not wear the Pahlavi Crown and instead wore a military hat to which the Darya-e Nour Diamond was attached, a new dress code emerged. In 1927, the Reza Shah military hat changed to the Pahlavi hat and replaced the traditional hats and turbans.

At that time, the chador turned into a political signifier and wearing it was considered a crime. During the Second Pahlavi Era, the dress code policies underwent changes and the regulations that had sought to efface distinctions in the clothing were replaced by the policy of diversifying the clothing trends. Gradually more and more European and American-style clothing such as suits and ties for men and relatively long skirt coats for women became trendy. However, since the 1960s and especially during the 1970s, transparent and erotic dresses for women became popular. At that time, uniforms in military and organizational units, as well as the schools, became almost widespread, but the streets witnessed a variety of clothing trends. The advertising industry in Iran has expanded and “young people began turning to fashion styles promoted by movies.” Soon, the destructive effects of such styles became visible at the community and family levels.

Revolutionary Fashion

It had been only twenty-four days since the victory of the Islamic Revolution that the issue of covering and hijab outlined a boundary among the revolutionaries. In his speech at the Refah School, the Leader of the Islamic Revolution stated: “It is all right for women to enter ministries, but if they work there, they should put on the religious clothing.”

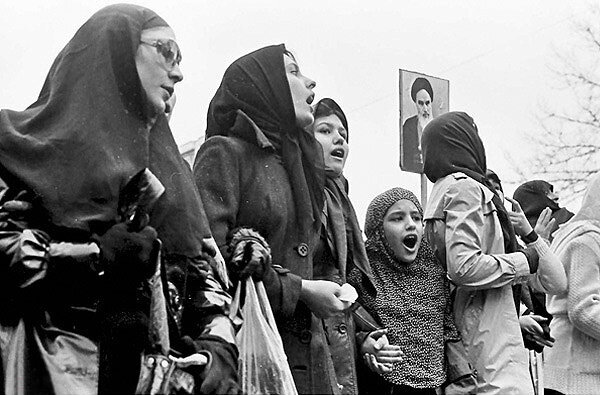

Religious and non-religious women from all walks of life used the chador and Islamic clothing to show their opposition to the Pahlavi regime. The black colour of the chador was a symbol of the unification and harmony of the society in the struggles against the regime. In this way, the body of women became politicized because of the hijab, and the call for returning to the hijab was a call for resistance to the prevalence of the Pahlavi cultural norms and the Western modernization policies of the Shah. At that time, people were turning away from all the Pahlavi emblems including the ties and bow ties. With the advent of the Cultural Revolution, clearer views on Islamic clothing were expressed. The designers were trying to change the organizational clothing style into an Islamic one by increasing the number of pleats at the shoulder of the dress, covering the shape of the body, and adding cuffs to the sleeves.

The physical fitness and uniformity of clothing in this period, conformed not only to the religious discourse, based on which the body was degraded by promoting the loose and pleated clothing but also to the revolutionary homogenization. The predominance of political discourse on dress codes led to the hijab becoming a symbol of revolutionary and religious struggles.

During this period, the religious discourse on clothing was predominant and men became interested in the simple clothing style of the seminarians. Take for example wearing white shirts over pants or shirts with short collars which resembled the clergy’s robes, along with having rosaries and agate rings.

Although it was permissible for women to wear the manteau (a long coat), they began wearing black chadors because of the charismatic position of the leader of the Islamic Revolution who considered the chador as the best and superior example of the hijab. In this way, the chador, from the perspective of the dress code, is considered the most complete religious signifier which indicates a sense of chastity and Islamic modesty.

Aversion to Fashion

After the war, many developments occurred in the field of clothing in a way that raised concerns as a “cultural invasion.” The policy of homogenizing and unifying the clothing styles was no longer pursued and hence the semantic meanings of clothing changed. The chador was a symbol of resistance and struggle in the early years of the Islamic Revolution, and afterwards, during the 1980s, it symbolized religion. Furthermore, in the early 1990s, it gained significance as a reflection of the tradition. In 1994, Ayatollah Khamenei stated: “The chador is our national symbol. It is more of an Iranian hijab than an Islamic one. The chador belongs to our people and it is our national garb.”

In the early 1990s, women returned to the field of economic activity and increased their social presence in universities and public activities; manteaus with puffy shoulders were a legitimizing sign of the presence of women in the public arena. Later on, the manteaus with loose sleeves became trendy.

Fashionism

Because the normativity of clothing that had dominated individual choices was reconsidered, people enjoyed more freedom in choosing their clothing. For example, the girls’ dress code at schools was revised on July 22, 2000.

Gradually, personal tastes and individual choices in some groups of the society turned the hijab into an aesthetic concept thereby allowing making small changes in the field of covering and prevailing norms. Adornments that were added to the clothing gave the manteaus a personal aspect. After that, making the sharp cuts in the collar of the dresses as well as shortening the scarves and the manteaus changed the boundaries of the dress code.

The manteaus, pants, and socks became shorter and clothing, instead of covering the body, was used for beauty. But due to the inconsistency of such clothing styles with the cultural atmosphere of the country as well as their adverse effects, the social and cultural consequences of them, the first one of which was various court cases relevant to social crimes, were soon appeared in the society.

The officials began sharply criticizing the general orientation of the society regarding clothing. Because in the view of those who had traditional tendencies, that phenomenon has led to the violation of the customary boundaries of clothing, and for the ones with religious affiliations, it has caused the decline of public chastity. In addition, some of the political officials also expressed their concern over the general dress code trends in society because of the decline of the policy of homogenizing and unifying the clothing styles which was rooted in their normativity.

In the 2000s, the manteau, which had been used as a homogenizing, unifying and formal female cover during the 1990s, became an aesthetic clothing trend by the means of the creation and innovation that took place in the pattern, sewing and fashion design.

Islamic Fashion

In 2003, the Supreme Leader approved fashionism to some extent: “You should not think that I am opposed to fashion, diversity and development in lifestyles. If pursuing fashion is not done at an excessive level, if it is not done out of childish competition, then it is alright. Dress codes, behaviour and one’s appearance change and there is nothing wrong with this, but you should not follow Europe in this regard.”

The Supreme Leader acknowledged fashion and fashionism, and therefore this remark became a turning point in the design of national clothing and fashion discourse.

He said: “I am very much in agreement with the fashion that has originated from our country. Because fashion means creativity and innovation, not something that comes from another country. Our fashion, clothing and the way of speaking are all imported from other countries... We should have Iranian clothing that is trendy, not old-fashioned like the clothing that belonged to the times of Achaemenid or Sasanian Empires.”

This view created a lot of hope in organizing the diversity of clothing. Eventually, the issue of diversity in clothing was recognized and acknowledged. Therefore, resolving the issue of national clothing depended on dealing with the issue of “fashion and diversity of clothing.” There were sources of national identity for designing the clothing including the ethnic clothing, the historical clothing style such as the clothing related to the Qajar period, as well as the Arab clothing e.g., the long robes. However, what was presented as the national chador was mostly taken from the contemporary Islamic clothing common in Lebanon and Egypt and lacked the historical symbols and the emblems of ethnic diversity.

The Analytical Model for Social Modifications of the Dress code

|

Turning away from Fashion After the Revolution and during the war (1980s) |

|

Fashionsim (2000s) Reform Period |

|

Islamic Fashion (2010s) Principlism Period |

|

Fashion Aversion Construction Period (1990s) |

Paradigmatic Modifications of Fashion in Post-Revolution Iran

|

Paradigmatic Model |

Contexts and Causative Conditions |

Phenomenon |

Consequence |

Actor and the Strategy of Action

|

Limitations and Interfering Conditions |

|

Revolutionary Fashion |

After the Revolution and during the War |

After the Revolution and during the War |

The chador for women and emphasizing the simplicity of the male dress code |

Revolutionary unifying institutions and the revolutionary committees that sought to fight against the manifestations of tyranny |

Seeking the revolutionary homogenization of the clothing styles by choosing the religious chador and trying to eliminate the manifestations of tyranny; the general condition of the revolutionary society |

|

Fashion Aversion |

Construction Period |

Traditional/formal hijab |

Policies for controlling the body with an emphasis on the formal dress and hijab as the cultural Iranian tradition |

Fashion as a manifestation of cultural invasion, establishing the centers for implementing the concept of enjoining the good and forbidding the evil, implementing the dress code policies |

More engagement of women in society and the efforts of the Construction Government to gradually change the dress codes |

|

Fashionism |

Reform Period

|

Aesthetical hijab/ violating the norms of clothing |

Abandoning the formal discourse by using a variety of clothing and makeup, and paying attention to bodybuilding and transparent clothing |

The media coverage of clothing and its diversity; the policies of tolerance and leniency for choosing the clothing |

Clothing is a manifestation of individual choices and political freedom |

|

Islamic Fashion |

Principlism Period

|

Normative/national hijab |

Re-implementation of dress code policies after studying the social problems that fashionism had caused |

Raising the issue of national clothing again and holding the Islamic fashion and clothing festival |

Determining the standard clothing style while taking into account the aesthetical aspect |

Reference: Bi-Quarterly Journal of Theoretical Principles of Visual Arts. Vol 1, No 2, Pp 95-107

Archive of Culture and Art

leave your comments