In the Name of God, the Most Compassionate, the Most Merciful

Author’s Note

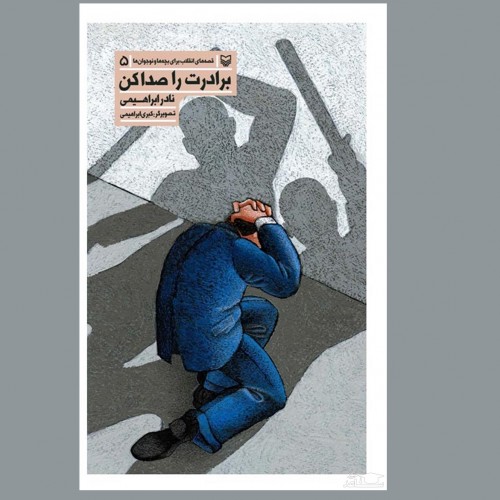

“The Stories of the Revolution” is a total of about twenty in number, and children play the main role in all of them. These stories were sent to me or entrusted to me by children from different parts of Iran at the height of our sacred revolution. They were either given to me through my acquaintances or were handed to me during my journeys all around Iran. In the climax of the revolution, these stories couldn’t be typeset. I arranged six of them and converted them from the simple report form to story form; I wrote them out with a pen and published them. These kinds of stories were called “white cover” back in those days because no one had the time to design and publish a nice cover. After publishing these six volumes, the serious post-revolution works began; I went to the Red Crescent Organization and worked day and night to start the “Red Crescent Volunteers Organization.” Afterwards, the entanglements and pressures of life didn’t leave me time to turn those glorious, bittersweet adventures into “stories.” I gradually arranged six more stories, but didn’t finish and publish them. The rest of the adventures and outlines were left unfinished.

This year – 1994 – the first five stories are being reprinted with the effort of “Hozeh Honari” in a beautiful format, along with illustrations. You are looking at it now. With hope in God, if I stay alive, I will publish the other six stories next year, on the anniversary of our great and glorious revolution. And if I remain alive for more, I might publish the other eight in the upcoming years.

These stories, which are about the nooks and corners of the biggest revolution in human history, are a dear memento; I want them to be left behind from me and the children who entrusted these notes and memories to me.

I had a faithful co-worker who helped me in the compilation of some of these stories and I would like to thank him. So, thank you, Mr. Shakour Lotfi.

And also, it wouldn’t be right to not thank the first publisher of this series; because back in those wonderful days, these kinds of works needed a lot of courage. So, with thanks to Farzin Publications.

Our revolution was such that even if hundreds of big books were written about it, it would still not suffice. These few small books are a dim star in the clear and unlit sky.

Thank you and goodbye

Nader Ebrahimi

November 6th, 1993

--

I’m sure, I’m sure that until the end of my life, I’ll cry whenever I see my father’s face. My mother says, “Enough, Masoumeh! It’s enough! Everything is over now. You should be thankful to God that your father is still alive.” But I can’t stop crying. I can’t.

When my father notices that I’m looking at him, he turns his face. Sometimes, he gets mad and yells, “Why are you acting like this, Masoumeh? Control yourself! I feel sorry for you and I feel upset. Don’t you understand that the revolution succeeded and we won? Don’t you understand that we took revenge and beat them?”

But I just can’t stop crying. I swear to God, I can’t. I can’t control myself. I’ve decided for a hundred times to look at my father’s face and smile. But when I look at his face and remember the bad, filthy, and horrible day, I can’t control myself anymore. You had to be there to see and know what I saw and what I went through.

My mother tells my father, “This girl is out of her mind. She has lost her wits. We have to take her to the doctor!” and my father nods his head in a way that you can’t tell whether he’s approving or rejecting my mother’s words. After all, he remembers that day too. I guess many people in Jahrom remember that day. The good, revolutionary people of Jahrom.

***

My father and I left the house in the morning, like always, to go to the streets and demonstrate; we went to shout “Death to the Shah!” and “All Hail Khomeyni!” I used to go with my father every day. My older brother, Mohammad, was on military service. When he got his diploma, he enrolled for military service and served in Jahrom itself. He came home to see us on some Friday nights.

(The revolution hadn’t started yet when Mohammad enrolled. If the revolution had started and Agha had ordered everyone to refrain from military service, Mohammad wouldn’t go either. But it was over now, and I don’t know why he didn’t want to run away either; now I know.)

On some days, my mother would wear her chador and come to the streets- if she didn’t have anything to do and left the house chores for the afternoon; but that day, it was just me and my father.

We went toward the bazaar. We used to arrange into groups there and started off. My father liked to greet a few people and talk to them about the daily news. Not too many people had gathered yet.

***

The circumstances in our city were very chaotic in those days. Two days back, men with clubs had set my father’s shop on fire. They had destroyed and burned down many of the other shops too. My father used to say, “It’s the last word. The last word must be said firmly. If we give in this time too, we’ll be wretched for another thirty years. We’ll be slaves, captives, and helpless people. We will either kill or get killed with the last shot..” My father used to say, “I’ll give everything I have for Agha, let alone my shop. I’ll sacrifice myself for him too. These days, the one who stretches out a helping hand to rescue this country and this nation is dear to everyone; he’s everyone’s master and the apple of everyone’s eye.”

My father knew how to talk well, and the shopkeepers who knew him would listen to his words.

In short, things were in chaos. It was said that up until that day, twenty-nine people were killed in Jahrom. And they were all young; youths who were their parents’ hope. They were their family’s “breadwinners.” According to my father, “They were tulip buds.” Unopened tulips.

My mother used to say, “May God tear them into pieces that they tear our flowers into petals like that.”

Mr. Nejati, our neighbour, used to say, “These youths come to the field as though they have made an appointment for dying. And if they’re late, they’ll fall behind.”

My father would reply, “Whoever has honour is in the middle of the field these days, Mr. Nejati; no matter young or old.”

***

Just like I said, that morning, we went until we reached in front of the bazaar. There were no policemen, soldiers, or men with clubs. There were no tanks, shells, or trucks either. The people said, “They have retreated. They’ll be done with any day now.” And these very words gave them more courage and made them very happy.

We first began our work with the same previous day slogans:

“The most revolutionary man in the world,

Ayatollah Khomeyni!

The leader of the freedom movement,

Ayatollah Khomeyni!”

And

“Independence, liberty, Islamic government!”

“Independence, liberty, Islamic government!”

and

“Long live the way of the martyrs of truth!”

“Long live the way of the martyrs of truth!”

But then, people started to murmur, “Let’s go pull down the statue of the traitor the Shah!” and “Let’s turn the flimsy Shah upside down!” and “Jahrom doesn’t need a statue of shamelessness” and these kinds of words. Slowly and gradually, everyone warmed up and got excited.

I looked at my father’s face and recognized that he is happy about this.

Then, people started chanting a new slogan which I didn’t completely understand, but I could tell it was related to pulling down the Shah’s statue:

“May the head of the traitor Shah be hanged!

May the body of the traitor Shah be toppled!

May the head of the traitor Shah be hanged!

May the body of the traitor Shah be toppled!”

(I could never understand how these slogans are made and who makes them. I still haven’t understood. I guess everyone had turned into poets back in those days.)

Then, we started off toward the statue square.

It was morning and not too many people had gathered yet. As we moved on toward the square, people came from all sides and joined in. Some of them were shocked when they heard that we were going to pull down the statue of the Shah. As my father said, the Shah was the statue of horror, and many were still afraid of him – although they didn’t express this fear.

Well, if the men with clubs and the killers had allowed us to chant slogans and shout, they surely hadn’t permitted us to pull down the statue of their the Shah. Although almost everyone knew this, they still moved on.

***

Everything happened so quickly, you won’t believe it. I couldn’t even understand what happened and what went on. All of a sudden, they started shouting, “They’re coming! They’re coming! Run away! They’re here!” Others said, “Let’s not run! Let’s fight! Let’s fight! Why are you running away!” Some said, “Ya Ali! Ya Husayn! Ya Ali! Ya Husayn!” and the crowd dispersed and started running toward every direction.

My father and I were almost at the back of the row and the trucks were approaching from behind us.

I hope this never happens to you! The trucks arrived as quick as lightning; when they stopped, men with clubs, gunmen, and killers got off and started the attack. They were like a pack of hungry dogs.

There weren’t still too many people, but everyone was running. My father and I were still behind.

My father pulled my hand. We started to run. The men with clubs were right behind us.

We were still running.

We could do nothing but run.

My father wanted to jump over a ditch; I don’t know why his foot hit the side of the ditch and he fell to the ground.

He fell down and my hand slipped out of his hand. That was all.

Everyone was running away and getting far.

My father forced himself up. He turned his head and stretched out his hand to hold my hand again. I stretched out my hand too, but it was too late. It was already too late. Someone hit my father on the shoulder with a club. My father staggered and tilted to one side but didn’t fall down. He tried to run again. He pulled himself to the sidewalk, next to the rails.

The men with clubs arrived and surrounded him.

The gunmen were with them too. They stood in a semicircle beside the rails and my father was trapped in the middle of that semicircle. It seemed as though they had come only because of my father; as if he was the only one who wanted to pull down the statue of the traitor the Shah.

I was left outside the semicircle and tried to move forward; I couldn’t.

The killers were standing close to each other.

They attacked my father; in front of my eye; in front of my very eyes.

Ten blows, a hundred blows, a thousand. I don’t know how many. My father was standing and holding his hands on his head. And there were blows that kept hitting his head, one after the other. I saw his face and how it was crumpled. I saw his head and how blood poured from it.

I yelled, “Stop beating him! Stop beating him! That’s my father. For God’s sake, don’t beat him! Have mercy! Have mercy!” But no one heard my voice.

Nobody heard my voice.

No one came to the help of a girl whose father was being beaten like that. The crowd too had gotten far away.

There was no one around us to help. The stone Shah was the only one that was standing up there, watching. They were pounding my father on the head, on the shoulders, and in the stomach.

And I saw my father who gradually bent down, folded, kneeled, fell to the ground, and fell on the sidewalk pavement. And they were still beating. They were still beating.

Everything went by quickly, except for the beating of my father. It took a very long time. I don’t know how many minutes, how many hours, or how many years. I don’t know. By God, I don’t know. They wouldn’t let go of him. They kept hitting. I was screaming, crying, and hitting myself; but it was useless.

I guess they beat my father in place of all the people of Iran; in place of all the people who hated the Shah and wished for his death.

Through the curtain of tears that had covered my eyes, I saw my father’s face again through the killers’ legs. I saw his eyes that closed. And I saw him shrink, crumple, and become small. He crouched himself and I saw a boot the kicked his stomach. Then, the ones who were hitting left, shouting and cursing. When they were leaving, one of them beat me really hard on the head; my eyes went black, but it didn’t hurt at all.

All of them were the Shah’s servants.

I was left with my father; that piece of smashed meat.

I was left with my poor father who was lying motionless on the ground.

I was sure he was dead; that he had been killed. It was the last shot, right?

I wanted to run and sit beside him and put his head on my lap, but I couldn’t run.

My legs were shaking. My eyes went black. I wish they had killed me instead.

My father wasn’t young. He couldn’t endure being beaten.

My father wasn’t a bud. He wasn’t an unopened tulip.

My father couldn’t even move twelve flower pots in our own yard without getting a backache. My father couldn’t jump over a ditch very quickly. He couldn’t run very fast.

My father had stretched out his hand to take me with himself, but he couldn’t.

I sat down and pulled myself to his side. I felt like I was paralyzed. It was as though I didn’t have legs. A narrow stream of blood was flowing from my father’s head and was moving toward a tree that was planted by the sidewalk.

I got by my father’s side and looked at him.

I was sure he was dead; although there was no reason to be so sure. I sat and looked at him. I couldn’t touch him. I couldn’t talk to him. I couldn’t do anything. I don’t know why I wasn’t even crying anymore. I was just sitting and staring.

Then, I saw my father’s closed eyes moving. I saw them opening. And I saw them open; just a little. Just enough for me to know that he is alive. He looked at me; what a glance! It was as if he had awakened from a sweet dream; he looked at me and did something similar to smiling; but his bloodstained and painful face couldn’t smile; his lips moved, barely, and he quietly said, “Call your brother!”

My brother? What did he mean? I didn’t know what he meant and what he was trying to say. But my brother wasn’t there. My brother wasn’t within reach. I didn’t know whether my brother was in the village or the barracks. I couldn’t find my brother so quickly and easily.

I asked, “Are you alive, dad?”

He didn’t reply.

There was no need to reply. He was alive, after all.

Some time passed. I kept looking at him and felt so sorry for him. He quietly said again, “Call your brother!” and then his eyes closed. I looked around myself. I wanted to shout, “Help! Help! Someone help me take my father home! He is still alive.” but I couldn’t raise my voice. I didn’t have to shout anymore. Four people were approaching. They came until they reached beside my father’s head and looked at him. One of them sat and put his ear to my father’s chest. After a while, he raised his head and said, “This one is alive too.” The four of them picked him up and started off toward an alley.

The men’s clothes were bloody.

I said, “Our house is not this way.”

One of them said, “It’s okay, my dear. We’ll take him to our own house.”

The ones who took my father to their own house were very kind. They had brought a number of others too. They cared for them and nursed them as though they were their own close relatives. One of them- who I guess was a doctor- wrapped my father’s head wounds. The others helped too. Then they went to bring blood bags and other things. When they were leaving, they turned to me and said, “God willing, he will stay alive. Is there anyone you want to inform?”

I said, “Yes, my mother.”

They said, “Then hurry!”

I started off. But throughout the way, I was thinking of my father’s face. I remembered when he had put his hands on his head and slowly and gradually bent down. I was crying out loud; when I reached home, I was still crying.

My mother screamed, “What in the world has happened?” and she hit herself in the head. In the middle of my cries, I said, “Dad is alive.”

My mother shouted, “Then what has happened? What has happened, huh?”

I told her all that had happened. My mother wore her chador and started off. She was whispering prayers and crying all throughout. She suddenly turned to me and shouted, “Are you sure he is alive?”

I said, “Yes, Mother. He spoke to me.”

My mother didn’t ask what he had said for me to tell her that he had asked for my brother.

***

The nice and kind strangers kept my father at their own house. I sat next to his bed and watched him until night time. My mother would come and go; but soundlessly. The good strangers said, “No one should know that we have turned this place into a hospital. If they find out, we are done for.”

All the while, I was waiting for my father to open his eyes, look at me, and perhaps smile. Near the afternoon, he moved a few times; but he didn’t say anything. Finally, near sunset, he opened his eyes a little and saw me. He mumbled something. I couldn’t hear. His lips only moved. I took my ear closer to hear. He said again, “Call your brother!”

I said, “Alright, dad. Alright! I’ll call him.”

The good strangers asked, “What does he want?”

I got up and went to the other room and said, “My brother is a soldier. He’s somewhere close by. Sometimes he goes to the village and sometimes comes to the city. I don’t know how to find him. My father has told me to call him a few times now. This is what he said right now too.”

They said, “It’s okay. In the morning, we’ll send you to the barracks with two boys the same age as yourself. You might be able to find him. We can’t show ourselves.”

***

What’s the use of telling you what I went through on that horrible night? What’s the use of telling you about the heavy pain that was aching my heart? Like my mother, you’ll probably say, “It has passed now and it’s over. Your father is alive too. Forget about it!”

How can I ever forget about it?

That night, that horrible night, the worst night of my life, I fell asleep and startled up a hundred times. Every time I fell asleep, I dreamed of my father who held my hand, ran, fell down by the ditch, forced himself up with pain, and held his hand out to hold my hand again; but he couldn’t. Limping, he pulled himself beside the rails and the men with clubs arrived and started hitting. In that corner, next to the rails, they hit, and hit, and hit. Ten people, a hundred people, a thousand people.

I saw my father looking at me. He had put his hand on his head and was looking at me from down there. Then he bent, kneeled, and fell down. I wanted to go to him, but I couldn’t. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t move any closer. I woke up and began to cry. Then I fell asleep again and had the same dream and woke up again. Sometimes, I only saw my father’s face and his lips which moved and he said, “Call your brother! Call your brother! Call your…”

Dear God! Take our family’s revenge from the Shah!

Do something that a thousand men with clubs attack him and hit him so hard that he is crushed!

Do something so that all his children are on his side but none of them can help him.

Dear God! Do something so that the Shah gets a taste of all the pains he caused for our people, then let him die.

***

Early in the morning, I went to the barracks with two young boys who were sent to accompany me. The three of us stood beside the big gates of the barracks. The boys pretended to be selling candy and chewing gum and these sorts of things and they played around. Their happiness and playfulness made me feel a little better. They told me, “Candy, Ma’am! Chocolate! Chewing gum, Ma’am! We have imported cigarettes too!” Then they burst out laughing. I was happy that they were happy. Sometimes, when someone was passing by, the boys ran up and said, “Candy, sir! Chocolate, sir! Sir, we have imported chewing gum too!” Then, they moved closer and said, “Excuse me, sir! We’re looking for Mohammad. His father is sick. May God keep your father safe. His father isn’t feeling well at all. For God’s sake, please tell us if you know where he is. Something might happen to his father, God forbid, and God will hold you responsible, sir!”

Some of them didn’t even answer. Some of them gave silly answers. And some of them thought for a while, bought a pack of chewing gum, candy, or something else, and mumbled, “We don’t know such a person.”

Finally, near noontime, we found someone who told us, “I know him. I’ll inform him. Get back to your work!”

One of the boys said, “This is our only job, sir! I promise, sir; I’m telling you the truth. We’ll wait for you right here. We’ll go over there! That way! But we really have to talk to him. Only a couple of words, sir! For the sake of whoever you love, please help us, sir! Don’t disappoint us, sir! Look at this poor girl, sir! This is Mohammad’s sister. Have mercy on her.”

The man said, “You tricksters! Let me see what I can do; but if you’re not looking for trouble, get away from here! Go to the other side!”

One of the boys said, “Yes, sir! Candy! Chocolate! Cigarettes! We have imported chewing gum too, sir. Do you want anything, sir?”

The man smiled, bought a pack of chewing gum, and left.

The other boy burst into laughter and fell to the ground. I asked, “What happened?” He said, “Instead of saying, ‘Candy! Chocolate! Chewing gum! We have imported cigarettes too!’, this idiot says, ‘Candy! Chocolate! Cigarettes! We have imported chewing gum too!.’” Then he sells the Iranian chewing gums in place of imported ones. The two of them laughed so hard that they got tears in their eyes. I was happy that their father wasn’t smashed with clubs; but then one of them said, “We are orphans. We neither have a father nor a mother. And our older brother was sacrificed for the sake of the revolution three months ago.”

***

Half an hour later, Mohammad showed up. I remembered my father’s face again and started crying out loud. The boys said, “Control yourself, kid! They’ll make us wretched!”

Mohammad approached. When he saw me, he suddenly burst into tears.

I said, “Brother! Dad wants to see you.”

He said, “Tell me the truth, Masoumeh! Has our father been killed?”

I said, “No, he is alive; but the Shah’s men with clubs beat him up in the demonstration. All his bones are broken; from his wrist to his forehead. He keeps saying, ‘Call your brother! Call your brother!’ When he comes round, he says this and falls unconscious again. I don’t know what he means.”

Mohammad said, “Go say I called him. Say I called him and he heard. Just say this!” Then he sat, embraced my head, cried with me, and said this a few times, “Forgive me, Masoumeh! Forgive me!” And the boys who were laughing and playing until then started crying too.

In the middle of his tears, Mohammad said, “Don’t worry, Masoumeh!” but I could tell how worried he was himself. The colour of his eyes had already changed; they were completely red. Then he stood up. His eyes were looking at the horizon. He turned and left without saying goodbye. I shouted, “Brother! You have to come and see dad!”

But he didn’t turn back again.

We waited until he went into the barracks.

***

I got back, sat by my father, and watched him until he moved again and opened his eyes. The doctor asked about his health in a loud voice, “Sir! Sir! Are you okay? Can you hear me well? If you can hear me, nod your head a little!”

We were all waiting.

My father barely moved his head. The doctor smiled and said, “He is conscious. He will stay alive to come to the ground again. Now, his life isn’t his own anymore.”

My father turned his eyes to look at me. He found me and didn’t take his eyes off of me.

I said, “I called him. Mohammad said, ‘Tell dad I heard his call. Rest assured.’’

***

The next day, at nine o’clock in the morning, a noise went up from the entire city all of a sudden. What a noise! The good strangers left too. My mother and the strangers’ mothers were the only ones left. After some time, they left too and trusted the injured ones to me. Some of the injured ones who were feeling better were sitting up. One of them said, “Turn on the radio, girl!”

I said, “I don’t know how. This is not our house.”

Then the door was opened and the strangers, boys, and women returned one after the other.

The strangers who had arrived before everyone else were very happy. They came into the room and said to my father, “Good news, Father! Good news! We took revenge on the kids who were martyred yesterday. We took the revenge of all the martyrs of Jahrom. Father! The people killed Jahrom’s military governor and chief of police.”

Father opened his eyes and smiled.

The strangers said, “They were shot from the top of a building across the police station. They say that one or two people fired at the jeep carrying the military governor and the chief of police with a machine gun.”

I quietly looked at them and listened.

Dear God! Was it possible?

The newspapers wrote the news and all the people of Iran were informed. “Jahrom’s military governor and chief of police have been killed. A graduate soldier from Jahrom was charged for the killing and was arrested.

My mother found out. The good strangers found out too. My father and I knew from long ago too, right?

I’m sure, I’m sure that until the end of my life, whenever I look at my father’s face, I will cry. My mother says, “Enough, Masoumeh! It’s enough! Everything is over now.” But I can’t stop crying. I can’t.

Mohammad says, “Masoumeh! Be a little considerate of us! We have feelings too. We feel sorry for you. Don’t do this!” But I can’t. By God, I can’t.

The boys come to the door and yell, “Candy! Chocolate! Cigarettes! We have imported chewing gum too!”

I wipe my tears and go to talk to them.

Archive of Culture and Art

leave your comments